Watergate, Wiretaps, and the White Panther Party

How Nixon’s dirty tricks against the radical left backfired and caused his downfall

BACKGROUND: REVOLUTIONARY SITUATION

On January 20, 1969, on the same day that Richard Nixon was sworn in as president, the Black Panther Party’s Breakfast for Children program began.

Breakfast for Children program, 1969 (Photo: Ruth-Marion Baruch, The Vanguard: A Photographic Essay on the Black Panthers, Beacon Press, 1970)

J. Edgar Hoover proclaimed that “the “Breakfast for Children program represents…potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.” Although this statement has been jeered at over the years, in fact Hoover realized that the Panthers were doing in America what the U.S. had failed to do in Vietnam: winning the hearts and minds of the people.

1968 had been a watershed year for radical movements in the United States. To cite only a few events: 221 major demonstrations took place in the first half of 1968. The Black Panther Party (BPP) and SNCC formed an alliance in February. Women protested the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City. Students at San Francisco State went on strike after a teacher who belonged to the Black Panther Party was fired; the strike lasted for five months. The infamous Democratic Convention took place in August. In October a poll revealed that 368,000 college students considered themselves revolutionaries. By the end of 1968 the BPP had 25 chapters and over 2,000 party members. In Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton was forming an alliance with an infamous street gang, the Blackstone Rangers, turning them away from crime and toward political activism. At the Olympics in Mexico City, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists and made history.

Revolution was in the air.

The government reacted with alarm. The new Attorney General John Mitchell vowed that the Justice Department would “wipe out the Black Panther Party by the end of 1969.” “Early in 1969, the President drew up contingency plans to cope with a possible uprising in the United States.”

The seeds of Richard Nixon’s fall from grace were already sprouting, a consequence of his fear of the radical left.

SCHEMES OF NIXON AND THE F.B.I. TO DESTROY RADICAL MOVEMENTS

Nearly all of the books about Watergate or Nixon − and there are literally hundreds − give extremely short shrift to the role of the radical left. They ignore the strength of the movements and the growing revolutionary fervor in the United States, and Nixon’s intent to destroy them. These writers also ignore the June 1972 Supreme Court ruling in the White Panther Party case that warrantless wiretaps were unconstitutional. Yet that ruling sent Nixon’s men into a frenzy of action that included removing listening devices, burning documents, erasing tapes, and even shredding money − a criminal conspiracy that toppled the presidency.

For citations and notes to all facts and quotations in this article, see Notes & Sources to Watergate, Wiretaps, and the White Panther Party https://www.necessarystorms.com/home/notes-and-sources-to-watergate-wiretaps-and-the-white-panther-party

The radical left was, in fact, a major concern of the Nixon administration. J. Edgar Hoover had quite a head start, having put COINTELPRO into action in 1956. Its original target had been the Communist Party USA, but almost immediately Hoover reclassified the civil rights movement into COINTELPRO. And even though the FBI never abandoned its campaign against the CPUSA, by the late 1960s the FBI’s focus was on black organizations (which it designated as “Black Nationalist-Hate” groups), especially the Black Panther Party.

Hoover’s memo of November 25, 1968 ordered field offices to “submit ‘imaginative and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP’.” On January 30, 1969 he ordered expansion and intensification of the effort to “destroy what the BPP stands for.”

While surveillance, harassment, infiltration, prosecutions, and even instigation of murders of Panthers were at the top of the FBI’s agenda, it didn’t neglect other radical leftists. In late 1968 a memo to all field offices admonished their failure to “seek specific data depicting the depraved nature and moral looseness of the New Left” which could be used to “neutralize them.”

Nixon was “desperately worried about radicals and violent anti-war groups,” and believed that his administration “would have been ‘out of our minds’ not to spy on left-wing Americans.” He later told Hoover that “revolutionary terror” represented the greatest threat to American society. But Nixon wasn’t as worried about a few random bombings as he was about a revolutionary situation becoming more so.

Throughout 1969 the movement did grow. Among the events that year: the Panthers set up the United Front Against Fascism, the American Indian Movement led the occupation of Alcatraz, the first Venceremos Brigade went to Cuba, GIs rebelled at Army bases in the U.S., American soldiers in Vietnam refused orders, and anti-war Moratoriums were held on October 15 and November 15, the latter drawing over half a million demonstrators to Washington DC. The Stonewall Rebellion was spontaneous but surely inspired by the revolutionary spirit of the times.

Attacks on the radical left also increased throughout 1969, ranging from city governments passing anti-commune ordinances to outright murders instigated by the FBI through manipulation and lies (such as the January 1969 murders of Los Angeles Black Panther Party members John Huggins and Bunchy Carter by the US organization) or carried out by police with help from agent provocateurs, informers or saboteurs (such as the December 4 assassinations of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark by Chicago police relying on an FBI infiltrator who provided a map of the apartment and slipped knockout drugs into Hampton’s food).

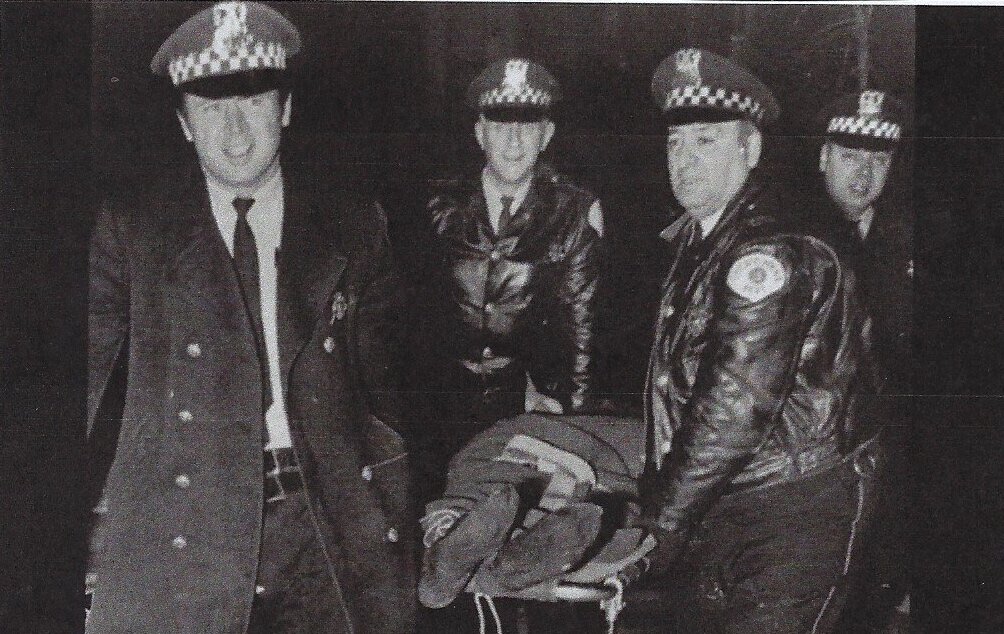

December 4, 1969: Chicago police laughing as they carry the body of Black Panther Fred Hampton after they murdered him. (Photo: AP)

On April 26, 1970 Nixon authorized American combat troops to cross the border from South Vietnam into Cambodia. He addressed the nation on April 30, announcing his decision. His attempt at justification was futile; protests immediately broke out across the country. 30 ROTC buildings were burned down or bombed. The National Guard was sent into dozens of campuses.

On May 4, Ohio National Guardsmen opened fire on protesters at Kent State, killing four and injuring ten. Eleven days later police fired on student protesters at Jackson State University, killing two and injuring fourteen. Ensuing protest marches drew hundreds of thousands in Washington and San Francisco.

One of the most astonishing protests ever held in this country began as a response to the invasion of Cambodia that gained urgency after the Kent State and Jackson State killings: a student strike that ultimately shut down over 880 colleges and high schools across the country. Over four million students went on strike. Little known today, this strike was unprecedented and continued for weeks, joined by professors and even some administrators. Thousands of students “moved from apathy to activism.”

Just after the Kent state killings, Nixon told a television interviewer that Kent State was “tragic,” then strongly implied that violence by protestors had triggered the shootings. White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, one of Nixon’s most trusted confidantes, wrote in his diary on May 4 of Nixon:

“He’s very disturbed. Afraid his decision set it off, and that is the ostensible cause of the demonstrations there. Issued condolence statement, then kept after me all the rest of the day for more facts. Hoping rioters had provoked the shooting, but no real evidence they did, except throwing rocks at National Guard.”

A less restrained view was expressed by Nixon in 1971 when he said to Haldeman:

“You know what stops them? Kill a few….Remember Kent State?”

Haldeman’s diary and the White House tapes reveal that Nixon continued to worry about the effects of the Kent State killings and the campus shutdowns. Nixon’s Staff Assistant Tom Charles Huston later testified that in 1970:

We were sitting in the White House getting reports day in and day out of what was happening in the country in terms of the violence, the bombings, the assassination attempts, the sniping incidents − 40,000 bombings [sic], for example, in the month of May in a 2-week period [and an average of] six arsons a day against ROTC facilities….we convinced ourselves that this was something that was going to just continue to get worse until we reached the point where all of the people who were predicting police-state repression…was going to become a self-fulfilling prophesy…As for example, I suspect it had been true in the Chicago Black Panthers raid, and in the Los Angeles Black Panther shootout. So my view was that we had to do something to stop it.”

Despite the FBI’s efforts against the radical left, Nixon was not satisfied. Huston said that on June 5, 1970:

“President Nixon called in J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, Richard Helms of the CIA, and others from military intelligence agencies [NSA and Defense Intelligence Agency]. He charged them with getting better information on domestic dissenters, and directed them to determine whether [leftists] were subject to foreign influence.”

This group became the ad hoc Interagency Committee on Intelligence (ICI). Huston was the White House liaison. Nixon was “concerned with making sure that the intelligence community was aware of the seriousness with which he viewed the escalating level of revolutionary violence.” In summer of 1970, “the entire intelligence community…thought we had a serious crisis in this country…we had to do something about it.”

Nixon signs the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, assisted by Attorney General Mitchell and the head of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Jack Ingersoll. On the Navy Seals website, this photograph is captioned “That’ll teach those hippies!”

The ICI met four times and produced a 43-page document that became known as The Huston Plan. It called for surveillance, break-ins, IRS harassment, use of informants (and allowing informants as young as 18), opening of mail, and more. On July 23, 1970 Nixon ordered immediate implementation of the plan.

For decades it’s been believed that the Huston Plan was shelved a few days after its implementation. Huston told the Church Committee in 1975 that Hoover and Attorney General Mitchell urged Nixon to withdraw his approval, and that he did. But is that true?

Some say that it was put into effect. Journalist Tad Szulc writes that although Nixon “subsequently claimed that he had this order rescinded within five days, on July 28, but there is no record of such an action.” And, as Szulc points out, eleven months later the White House created its own secret investigative unit. Furthermore, in a subsequent prosecution of the Weathermen, the government dismissed charges rather than disclose how it had obtained evidence, and the defense lawyer told reporters that “the hearing would have shown that the 1970 [Huston] plan…had actually been put into effect.”

Tom Charles Huston and President Nixon

Just as significantly, it should be remembered that all of the agencies participating in the ICI had been conducting such operations for two decades. The true purpose of the Huston Plan was to obtain presidential sanction for those operations.

The Huston Plan remains classified “Top Secret” to this day.

In an Oval Office conversation on May 5, 1971, Nixon and Haldeman discussed ways to stop protestors. Haldeman noted that Charles Colson had “got a lot done that he hasn’t been caught at.” Colson, the White House Special Counsel and Nixon’s “dirty tricks” man, had instigated hard hat workers in New York to assault anti-war protesters right after Kent State, and Haldeman now suggested the White House could have Colson use his Teamster connections to hire thugs. “Murderers…that’s really what they do…regular strikebusters types…they’re gonna beat the [obscenity] out of some of these people…” Nixon was enthusiastic and said the thugs would “go in and knock their heads off.”

The Pentagon Papers were published in June 1971. They damaged Nixon not at all since they concerned US policy in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967, but were of great concern to his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, whose role in the Vietnam War went back to the JFK administration. Kissinger convinced President Nixon that the leaks had to be stopped; if not, Nixon’s own secrets could be revealed. Thus came the formation of the so-called Plumbers’ Unit at the White House, whose main actors were G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent, and E. Howard Hunt, a former (or not) CIA operative. One of their first actions was to break into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in September 1971.

That summer presidential staff assistant Jack Caulfield (a former NYPD officer who’d worked in the notorious anti-radical unit BOSSI before joining the Nixon Administration) set up a clandestine intelligence-gathering operation within the White House named Operation Sandwedge. Its objective was to insure Nixon’s re-election. To that end, the anti-war movement was an especial target for the proposed surveillance.

But White House counsel John Dean, Haldeman, and others soon grew disappointed with Sandwedge; it wasn’t accomplishing enough. The operation was turned over to G. Gordon Liddy, who renamed it Operation Gemstone and expanded its scope. Plans ranged from intelligence gathering to kidnapping to using “chase planes” to intercept messages from prominent Democrats. Incredibly, Liddy put the entire plan in writing. He even had letterhead made. He and Hunt also arranged for the CIA to draw up a professional diagram of Gemstone.

Another strategy of the Nixon administration was to keep the radicals tied up in court. By 1970 this strategy reached fruition as radicals across the country were arrested and put on trial, tying up money in bail and attorneys’ fees and shifting the focus of their organizing.

RADICALS IN ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN

John Sinclair was a long time political activist, poet, and founder of the Detroit Artists Workshop. With others he created the Trans-Love Energies (TLE), a political commune whose activities included publishing a newspaper, creating a poster printing operation, and putting on concerts. John was also a marijuana advocate. He was arrested in January 1967 for giving two joints to someone who turned out to be a cop. It was his third marijuana arrest. Trial was pending when the TLE moved to Ann Arbor in June of 1968.

John Sinclair (Photo: sensiseeds.com)

In October of 1968 the White Panther Party was created as the political wing of the TLE, in response to Huey Newton saying that Panthers were needed in white communities.

Among the neighbors of the TLE commune were members of a rock band, the MC5. John Sinclair became their manager. The band signed with Elektra Records on September 26, 1968.

Two days later, a clandestine CIA office in Ann Arbor was bombed.

In January 1969, the month of Nixon’s inauguration, the MC5 album “Kick Out the Jams” was released and immediately entered Billboard’s Hot 100. John Sinclair had written the revolutionary liner notes.

“…we demand a free music, a free high energy source that will drive us wild into the streets of America yelling and screaming and tearing down everything that would keep people slaves...”

“Kick Out the Jams” cover, original artwork by Gary Grimshaw

Within weeks, Elektra censored the MC5’s music and removed the radical liner notes. The band quit Elektra.

In June of 1969, young people and Ann Arbor police clashed on the streets. The White Panther Party (WPP) put out a leaflet calling for the street to become a pedestrian mall and alluded to People’s Park in Berkeley. The so-called Ann Arbor Riots lasted for three nights. These events caused the FBI to become very interested in the WPP. Hoover was already angry about the MC5’s lyrics, which he called “filthy” and “obscene.” Now he ordered monitoring and disruption of the White Panther Party.

On July 25, John Sinclair was found guilty of possession of marijuana (the two joints he’d given away) and three days later was sentenced.

Addressing the court, John said:

“I don’t know what sentence you are going to give me, it’s going to be ridiculous whatever it is. And I am going to continue to fight it. And the people are going to continue to fight it, because this isn’t justice. There is nothing just about this, there is nothing just about these courts…”

The judge, Robert Colombo, disputed John’s position on marijuana, which Colombo called “narcotics.” He concluded:

“John Sinclair has been out to show that the law means nothing to him and to his ilk. And that they can violate the law with impunity, and the law can’t do anything about it.

“Well, the time has come. The day has come. And you may laugh, Mr. Sinclair, but you will have a long time to laugh about it. Because it is the judgment of this Court that you, John Sinclair, stand committed to the State Prison…for a minimum term of not less than 9-1/2 nor more than 10 years….”

Colombo closed the hearing by denying bail on appeal.

A few weeks later Leni Sinclair, other White Panthers, and some supporters went to the Woodstock Festival to talk about John Sinclair’s case. But when Abbie Hoffman went on stage and began to speak, The Who’s Peter Townsend hit him on the head with his guitar and Hoffman tumbled off the stage. Neither Hoffman nor the WPP was able to tell the nearly half a million people that John had just been locked up for 10 years for two joints.

With the WPP reeling from the blow of John Sinclair’s prison sentence, they were hit with a new injustice: on October 7, 1969, Panthers Sinclair, Pun Plamondon, and Jack Forrest were indicted and charged with conspiring to bomb the Ann Arbor CIA office. Pun was also charged with carrying out the bombing. He went underground and was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List until his arrest in July 1970.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon performing at the “Ten for Two” rally for John Sinclair on December 10, 1971. (Photo: sensiseed.com)

The WPP learned that one David Valler was the government’s star witness, the “unindicted co-conspirator” − a status the president would soon be sharing with him. Valler was known around the Ann Arbor area for carrying out eight bombings, which he openly bragged about, even calling the newspaper to claim credit.

In August 1970 an FBI agent completed a 107-page report on the WPP for J. Edgar Hoover, who named the WPP one of the most dangerous militant groups in the country. A few months later Nixon discussed the WPP with Hoover, Mitchell, and several members of Congress. Around that time, a Michigan State Police officer testified to the US Senate Judiciary Committee’s Internal Security Subcommittee on the danger posed by the WPP. His lurid testimony resulted in the memorable headline in newspapers throughout the country: “White Panthers Used Drugs, Sex to Promote Revolution.” The New York Times less salaciously headlined an alleged plot to kidnap VP Agnew and the next day reported, “White Panthers Call Charge of Kidnap Plot ‘Fabrication.’”

THE MITCHELL DOCTRINE

Previous administrations usually denied that they had wiretapped dissidents. The Nixon administration openly asserted that it had.

The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, known as The Wiretap Act, had been enacted in 1968 during the Johnson Administration. Nixon and Mitchell decided that the Act gave the president the authority to ignore constitutional rights and to order wiretaps of American dissidents if he, and he alone, determined that national security was at stake.

Architects of The Mitchell Doctrine. (Photo: NARA)

This theory became known as “The Mitchell Doctrine.”

On February 22, 1970 Judge Julius Hoffman ruled in favor of the Mitchell Doctrine in the Chicago conspiracy case. But on January 8, 1971 a federal judge in Los Angeles rejected the argument in the trial of a former BPP member.

Many radicals were currently on trial or soon would be. But the radical left’s activities were heating up and the Nixonians wanted to put an end to the movement sooner rather than later. They wanted a higher court — ideally, the highest court — to confirm their interpretation of the Mitchell Doctrine. In the normal course of things, a defendant’s challenge to the doctrine would be raised on appeal after trial and conviction; such appeals normally took a few years to wind their way through the appellate courts. But if the Justice Department lost a ruling on the doctrine before trial, during the period of discovery and pretrial motions, the appeal could be brought immediately, and even better, it could be brought by the Justice Department itself.

Nixon and Mitchell set their sights on the White Panther Party conspiracy case.

One of the WPP’s lawyers later wrote:

“We never knew how the Nixon-Mitchell White House/Department of Justice decided to pick this case in which to take a stand. Similar motions [for discovery of wiretap evidence] had been filed in other cases and Warren Ferguson, a courageous federal judge in Los Angeles, had ruled warrantless political electronic surveillance of U. S. citizens illegal in a BPP case. But that was post-trial, and the regular process of appeal was not going to be fast…The Government apparently wanted a rapid review….Plus, they knew that the tapes were irrelevant to the charges.”

The “contents [of the intercept] have never been disclosed,” but years later were revealed to consist of “six occasions of telephone surveillance involving the Black Panther Party in Berkeley and San Francisco, California, between February and July 1969...” Mitchell and Nixon chose this case to make their stand, so perhaps their strategy was to obtain approval of the warrantless wiretap of the BPP for “national security” purposes, while only having to disclose several calls between Pun Plamondon and people at the Black Panther office − probably over routine matters, since radicals were usually circumspect on the telephone.

“Both sides knew this was going to be an important case. The constitutionality of wiretapping laws was an open question, and the Attorney General’s office had passed on other potential cases to bring this one to the Supreme Court. It was the best chance the newly elected Nixon administration had of defending the practice of warrantless wiretapping.”

The three White Panthers were represented by National Lawyers Guild attorneys Leonard Weinglass (Sinclair), William Kunstler (Plamondon), and Hugh Davis Jr. (Forrest). The trial judge was Damon Keith, appointed to the federal bench in 1967 by President Johnson. Judge Keith was one of the few black federal judges and, based on his record to that point, he was not afraid to enforce the constitutional rights of disfavored citizens.

Late in 1970 the defense filed several motions, including one for disclosure of electronic surveillance. The prosecuting US attorney stated that he did not know of any such surveillance, but stipulated that he would turn over any that he learned of.

In fact, on August 19, 1970, Attorney General Mitchell had authorized a wiretap of the WPP. He did not obtain a warrant. The wiretap was installed on September 9.

Either the Michigan US attorney’s office truly didn’t know about this wiretap, or, because it had been installed after the incidents that gave rise to the criminal charges, considered it outside the scope of the stipulation. In any case, neither Judge Keith nor the defendants were told about it.

In December 1970, Attorney General Mitchell filed an affidavit stating that Pun Plamondon had been overheard on a wiretap of another radical group, without identifying it. Judge Keith ordered a full hearing and asked for briefs.

In their briefs the government propounded The Mitchell Doctrine: the chief executive has the inherent power to ignore the Constitution if he thinks it necessary for national security.

On January 26, 1971, Judge Keith ruled against the Justice Department. “The Court is unable to accept [the Government’s] proposition. We are a country of laws and not of men,” he wrote.

“Such power held by one individual was never contemplated by the framers of our Constitution and cannot be tolerated today.”

Damon Keith being sworn in as a federal judge in 1967.

The Justice Department had expected to lose and immediately appealed to the Sixth Circuit.

At around this time the White Panther Party disbanded its national organization and became the Rainbow People’s Party. Also, the White House taping system began to operate in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room.

On April 8, 1971, the Sixth Circuit upheld Judge Keith and denied the government’s request for a writ of mandamus, ordering that transcripts of the wiretapped conversations be turned over to the defense. Justice Edwards explained that 18 USC §2511(3) didn’t grant additional power to the president, and wrote:

“It is strange, indeed, that in this case the traditional power of sovereigns like King George III should be invoked in behalf of an American President to defeat one of the fundamental freedoms for which the founders of this country overthrew King George’s reign.”

That month, the Department of Justice petitioned to be heard in the United States Supreme Court. The conversation between Nixon and Haldeman described above (about having thugs assault demonstrators) was held on May 8. On June 21, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the wiretap case. The NY Times reported that

“John Mitchell has argued that denying the Government the right to spy on these groups would make the Constitution ‘a suicide pact.’ He contends that ‘never in our history has this country been confronted with so many revolutionary elements.’”

Throughout 1971, Nixon, Mitchell and others promoted wireless wiretapping − took The Mitchell Doctrine on tour, one might say. To name just a few of their appearances: Nixon spoke at the American Society of Newspaper Editors convention; Mitchell to the Virginia State Bar Association, the Kentucky Bar Association, and the David Frost show; and Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist to the American Bar Association conference (held in London, England).

President Nixon with new Supreme Court justices Lewis Powell (L) and William Rehnquist (R), December 22, 1971 (Photo: Nixon Presidential Library)

Rehnquist had been brought into the Justice Department in January 1969 by his good friend Richard Kleindienst and soon “gained a fearsome reputation as the department’s most ardent advocate of wire-tapping, government surveillance and preventive detention.” He had taken part in crafting The Mitchell Doctrine.

In October Nixon nominated Rehnquist and lawyer Lewis Powell to the Supreme Court. Nixon advised Mitchell to “emphasize to all the southerners [in Congress] that Rehnquist is a reactionary bastard, which I hope to Christ he is.”

Powell had published an article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch on August 1, 1971 headlined: “Civil Liberties – Fact or Fiction,” in which he wrote:

“The question is often asked why, if prior court authorization to wiretap is required in ordinary criminal cases, it should not also be required in national security cases. In simplest terms the answer given by the government is the need for secrecy…Court authorized wiretapping requires a prior showing of probable cause and the ultimate disclosure of sources. Public disclosure of this sensitive information would seriously handicap our counter-espionage and counter-subversive operations.”

“The radical left,” Powell continued, “strongly led and with a growing base of support, is plotting violence and revolution.” He concluded that “the outcry against wiretapping is a tempest in a teapot…Law abiding citizens have nothing to fear.”

Confirmation hearings were held in early November. Powell assured the Senate he could set aside his personal beliefs and follow the Constitution. “I would certainly consider the entire case in light of the Bill of Rights and the restrictions in the Constitution of the United States….” He was confirmed on December 6 by a vote of 89-1.

Two important events occurred on December 10: Rehnquist was confirmed 68-26, and the Rainbow People’s Party put on a “Ten for Two” rally for John Sinclair in Ann Arbor. Among the speakers and performers were Allen Ginsberg, Bob Seger, Commander Cody, Stevie Wonder, Bobby Seale, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono. John Lennon (in his first major performance in the U.S. since the breakup of the Beatles) had written a song about John Sinclair. Over 15,000 attended the event.

Two days later, John Sinclair was released from prison on bail pending appeal.

On January 28, 1972, Nixon ordered the creation of ODALE – Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement. ODALE combined the functions of various other agencies and could conduct searches, surveillance, audits, investigations, and “extraordinary missions.” It answered only to the White House. Congress was bypassed. Even the budget didn’t need congressional approval, as it would come from the Justice Department’s LEAA.

ODALE gave the Nixon Administration an excuse to expand domestic intelligence without oversight, and the wherewithal to do so.

Nixon’s Domestic Affairs adviser John Erlichman confirmed that those were the goals of the administration in a 1994 interview:

“You want to know what this [war on drugs] was really all about?” he [Erlichman] asked with the bluntness of a man who, after public disgrace and a stretch in federal prison, had little left to protect. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

“THE INTEGRITY OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH”

Justice Rehnquist, who had taken his seat on January 7, 1972, had recused himself from the wiretap case. Justice Powell remained on the panel, so Nixon and Mitchell probably assumed the case would be a slam dunk.

Friends of the Court briefs urging that the Sixth Circuit decision be upheld had been submitted by the ACLU, the United Auto Workers, the Black Panther Party, the American Federation of Teachers, and the American Friends Service Committee. No briefs were submitted in support of the government’s position.

Oral argument was held on Feb 24, 1972. Usually, the Solicitor General argued for the government before the Supreme Court, but this time Robert Mardian, who was in charge of Nixon’s anti-Left apparatus, appeared and argued.

Arthur Kinoy, one of the WPP’s appellate lawyers, wrote later that he was amazed to realize that Mardian and the Nixon administration were laying their strategy out in the open:

“Without hesitation or apology, Mardian demanded from the Court judicial approval for a course of conduct that would place the President, in Nixon, the unreviewable and absolute power to suspend the provisions of the written Constitution….It was one of the most dangerous moments in the long history of the Supreme Court.”

When Mardian began to speak Justice Thurgood Marshall turned his back, facing the wall. Near the end of Mardian’s allotted time, Marshall spun around and said: “Mr. Mardian, you keep ducking the Fourth Amendment. Are you ever going to get to it?”

Another justice asked Mardian what protection ordinary citizens had if the express words of the Constitution could be disregarded at will by the president. Mardian replied:

“The Court must…rely almost entirely on the integrity of the Executive Branch.”

At the moment Mardian was speaking those words, the Executive Branch was demonstrating its integrity by developing plans for mugging squads, kidnapping teams, break-ins, electronic surveillance, and more. That very day it had planted a false story in a newspaper in order to damage the strongest Democratic candidate for president, Edmund Muskie. It had already broken into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist; emplaced a spy as Muskie’s driver; created documents implicating JFK’s administration in the assassination of South Vietnamese president Diem; installed wiretaps on Cabinet and White House aides and newsmen suspected of revealing the secret bombing of Cambodia (the so-called Kissinger Taps); ordered the IRS to investigate political “enemies” and to drop audits of Nixon’s allies; planned physical attacks on anti-war demonstrators; and, last but not least, installed numerous illegal wiretaps on radicals.

The same month as the oral argument, Charles Colson asked Liddy to look into assassinating newspaper columnist Jack Anderson. On May 28, three months after oral argument, Nixon’s men bugged the office of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate. They had not obtained a warrant.

So much for relying on the integrity of the Executive Branch.

WARRANTLESS WIRETAPS HELD TO BE UNCONSTITUTIONAL

On Friday, June 16, 1972, the Supreme Court finalized its decision. The decision would be announced and the opinion published on Monday. Until then, it was supposed to be kept secret. The only people who are supposed to know in advance of any Supreme Court decision are the justices, their clerks, essential court personnel, and presumably typists, proofreaders, printers, and collators. But that is, after all, quite a few people. Also, drafts of opinions circulate among the justices for weeks, sometimes for months.

Theoretically, since Justice Rehnquist took no part in the decision, he didn’t know what it would be.

The White Panther Party, Arthur Kinoy, and William Kunstler all believed that Nixon learned on Friday that the Supremes would rule against warrantless wiretaps on Monday.

Kinoy writes that Nixon had expected a totally different result, and so:

“In haste and panic, files had to be deep-sixed or cleaned out, and the silence of wiretappers had to be bought…..The one thing which up until the June 19th decision it had been essential to show − presidential authority for the covert acts in violation of the Constitution − afterward became the one thing which had to be hidden at all costs.” (Emphasis supplied)

Late Friday night, five men broke into the Democratic National Committee (DNC) office at the Watergate while Liddy and Hunt directed the operation from a hotel across the street. The usual explanation is that the five men were making a repair to a defective bug. But when arrested, they carried four listening devices, not just the one supposedly malfunctioning device. Furthermore, they apparently risked sending five men to illegally break in to repair one bug. One man could have done that, perhaps with another to pick the locks.

Common sense tells us that the so-called Watergate burglars weren’t going into the DNC to repair a wiretap. They were removing listening devices that would, on Monday morning, be declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court.

The five men were arrested. Along with burglary tools and surveillance equipment, police turned up a key to a hotel room across the street, where they found almost $2,300 in sequentially numbered hundred-dollar bills and an address book linking the men to the White House.

Items taken by police from just one of the five Watergate “burglars” on June 17, 1972 (Photo from ABC News)

Monday’s ruling was reported the next morning in the New York Times:

“The Supreme Court has issued a sharp rebuke to those ideologues of the executive branch who consider the President’s ‘inherent powers’ superior to the Constitution.”

The vote was 8-0.

Not only did Justice Powell hold that warrantless wiretaps were unlawful − he wrote the strongly worded opinion.

“History abundantly documents the tendency of government…to view with suspicion those who most fervently dispute its policies. Fourth Amendment protections become the more necessary when the targets of official surveillance may be those suspected of unorthodoxy in their political beliefs.”

AFTERMATH

The day of the ruling, Attorney General Kleindienst issued a press release announcing that he had

“…directed the termination of all electronic surveillance in cases involving domestic security that conflict with the Court’s opinion.

Hereafter, surveillance will be undertaken in domestic security cases only under procedures that comply with the Court’s opinion…”

Rose Mary Woods demonstrates the position that she testified she held for five minutes, accidentally erasing some of the tape of the June 20 conversation of Nixon and Haldeman. Her leg is stretched as far as possible while her foot holds down the erase pedal as she answers a phone call. Another thirteen and a half minutes were erased by a party or parties unknown. In 2003 new technology established that between five and nine separate erasures had occurred. (AP Photo)

On June 20, 1972, the day after the ruling and three days after the Watergate break-in, Nixon and Haldeman held their first discussion about Watergate. It was recorded. In July 1973 Nixon refused to comply with a subpoena to turn over that and the other White House tapes. A few months later the the president’s lawyer announced that eighteen and a half minutes of the June 20 tape had been erased. Nixon claimed the erasure was accidental.

To date, the particulars of that June 20 conversation are unknown. White Panther lawyer William Kunstler later wrote that he believes the 18-1/2 minute tape erasure “implicated Rehnquist in leaking the impending wiretap decision.”

Nixon also talked that day with John Mitchell on what he called “an untapped phone.” The contents of that brief conversation are also unknown.

No newspapers or TV broadcasts connected the wiretap ruling to the Watergate break-in.

Ten days after the wiretap ruling, a Senate Judiciary subcommittee chaired by Senator Ted Kennedy held hearings to clarify the

“…Justice Department’s approach to wiretapping and bugging of Americans, especially dissenting Americans….The time for playing fast and loose with the Bill of Rights has come to an end.”

The Attorney General’s representative testified that while the office disagreed with the ruling, it would not, for the time being, seek legislation negating it.

On June 23 Nixon and Haldeman had a conversation that became known as the “smoking gun”: they planned ways to get the FBI not to investigate the Watergate break-in.

For the next two years the Nixon administration focused on the cover-up.

On July 28, 1972 government dropped the charges against John Sinclair, Jack Forrest and Pun Plamondon.

The WPP lawyer Hugh “Buck” Davis Jr. wrote that after the White Panther decision,

“Quietly all of the big conspiracy cases [against movement activists]….were dropped. The Government could not prove a single case without its illegally obtained evidence or else did not want to suffer further embarrassment and exposure of COINTELPRO, so they abandoned them. That is how the White Panthers and Judge Keith saved the movement from years of surveillance, COINTELPRO disruption and conspiracy charges.”

Buck Davis might be running away with his enthusiasm. The gist of his statement is true but in fact the government did not drop all its conspiracy cases. In July 1972 a Grand Jury was convened to investigate members of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War for allegedly conspiring to disrupt the 1972 Republican convention, and a year later the “Gainesville 8” were prosecuted. In August 1973, the jury took just three hours to acquit. The Camden 28 were tried in 1973 and also acquitted. Other radical leftists, while not charged with conspiracy, faced politically-motivated criminal charges. (More information is in the Notes.)

Almost exactly two years after the wiretap decision, on July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court issued another ruling against Nixon by an 8-0 vote, again with Rehnquist recusing himself. The court ruled that Nixon had to turn over tapes and other subpoenaed materials requested by the Watergate special prosecutor.

Nixon resigned sixteen days later.

CODA

Black Panther Party chairman Bobby Seale speaking at the John Sinclair rally on December 10, 1971. He had been in prison and/or on trial himself for several years. He was a defendant in the Chicago Conspiracy trial, where he was bound and gagged and chained to a chair when, after being denied the lawyer of his choice, he asserted the right to represent himself. His case was severed and Judge Julius Hoffman sentenced him to four years for contempt of court. (Judge Hoffman ruled in favor of The Mitchell Doctrine in that case.) Bobby was taken from jail and extradited to New Haven, CT and charged with the murder of a fellow BPP member, Alex Rackley. After a long trial the jury deadlocked 11-1 for his acquittal and 10-2 to acquit co-defendant Ericka Huggins. The judge dismissed charges in May 1971. In 2006 evidence revealed that the head of New Haven Police Intelligence Division, Nick Pastore, had recruited an informer to assist the infiltrator who actually murdered Alex Rackley. Pastore became Chief of the New Haven Police Dept in 1990.

David Valler, the admitted bomber, was never charged for bombing the Ann Arbor CIA office, nor was anyone else. During his time as a guest of the state of Michigan, Valler wrote newspaper columns espousing the evils of the counterculture. He was released from prison after charges were dropped against the WPP defendants.

In 1986 William Rehnquist was nominated by President Reagan to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. William Kunstler spoke at the nomination hearing and told of Rehnquist’s role in concocting The Mitchell Doctrine. “A man who will tell the president of the United States that he has the power to tap anybody’s phone without a warrant, without judicial authority, is not fit to sit as an Associate Justice, much less the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.” Rehnquist was confirmed by a vote of 65-33. He served until his death in 2005.

Mitchell and Mardian were both convicted and sentenced to prison for crimes relating to the Watergate cover up. Mardian’s conviction was later overturned and the prosecutors opted not to re-try him.

On July 1, 1973, President Nixon signed an order creating the Drug Enforcement Administration. ODALE was absorbed into it.

On March 9, 1972, John Sinclair’s marijuana conviction sentence − the infamous “ten for two” case − was ruled unconstitutional by the Michigan Supreme Court because it was cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The court also found that marijuana was not a narcotic and that “the ‘stepping-stone argument’ that marijuana use leads to use of ‘hard narcotics’ has no scientific basis.” This ruling resulted in some 130 prisoners in Michigan being freed. Michigan soon passed a law lowering the penalties for marijuana.

The Rainbow People’s Party worked with the Human Rights Party and elected members to the Ann Arbor City Council, which in 1972 passed an ordinance making possession of marijuana the equivalent of a traffic ticket, with a $5 fine. A year later the Republicans regained control of the council and repealed the measure, after which the Rainbow People’s Party was able to get it on the ballot in 1974. Ann Arbor voters approved. The NY Times referred to Ann Arbor as “the dope capital of the Midwest.”

In 2016, Detroit voters approved an initiative to change a zoning ordinance to allow medical marijuana facilities. Judge Robert Colombo Jr. − the son of the judge who sentenced John Sinclair to 9-1/2 to 10 years − overturned the new ordinance.

Judge Robert Colombo Jr. of Wayne County, Michigan, who followed in his father’s footsteps by making anti-marijuana rulings.

Until his death in 2024, John Sinclair continued his marijuana advocacy, wrote books, hosted jazz music on the radio, and performed as a jazz poet.

Pun Plamondon wrote a memoir about his time with the Panthers and his reconnection with his roots, Lost from the Ottawa: the story of the journey back. Pun died in March of 2023.

The three White Panther Party defendants in the wiretap case sued Richard Nixon, John Mitchell, Richard Kleindienst, Patrick Gray, and others in March 1973 for civil rights violations. Richard Nixon was dismissed as a defendant within weeks. In 1975 an order dismissing the remaining defendants on the grounds of qualified immunity was reversed because discovery had not yet been completed. That discovery revealed John Mitchell’s “supervisory role in the Black Panther Party surveillance and his motivations for authorizing it”; memoranda from J. Edgar Hoover to Mitchell seeking authorization for BPP wiretaps in 1969; and wiretapped conversations between John Sinclair and his attorney “which should never have been monitored.” But the case was dismissed in 1981 for insufficient action by the plaintiffs.

Judge Damon J. Keith at Howard University Law School in 2016. (Photo: Marvin Joseph for the Washington Post)

The Justice Department did not tell the White Panther Party defendants, their lawyers, Judge Keith or the Supreme Court about the wiretap installed on the phone at the WPP headquarters from August 1970 until January 1971. It had been removed the day after Judge Keith’s decision. The WPP only learned of it after making a Freedom of Information request in 1977.

Judge Damon Keith was named to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1977 by President Carter. Among his many cases over fifty years as a federal judge, the wiretap case (which is called “the Keith case”) was his best known. Among his other decisions were a 1973 order to the Justice Department to disclose its investigatory methods against the Weathermen and the upholding of the Detroit Police Department’s affirmative action program. In 2002 he ruled that the Bush administration could not conduct deportation hearings in secret using a blanket national security justification. Judge Keith died at age 96 in 2019.

In the Bush case Judge Keith had written, “Democracies die behind closed doors.” In 2017 the Washington Post adapted this and made it their slogan: “Democracy dies in darkness.”

Headline photo: Demonstration in front of the White House on May 9, 1970 (Bettman/Getty Images)