The Silencing of Martha Mitchell

“They were afraid of my honesty.”

Back in the early days of the Nixon administration, Martha Mitchell was detested by most of us radicals. She and her husband John, the Attorney General of the United States, embodied what we were fighting against.

Shortly after being appointed Attorney General, John Mitchell vowed, “This country is going to go so far to the right you won’t recognize it.” Martha’s voluble denunciations of anti-war demonstrations and her lobbying on behalf of a racist Supreme Court nominee didn’t endear her to those of us in the anti-war and civil rights movements. In fact, my friends on a communal farm in Oregon named their two pigs John and Martha.

But when Martha threatened to expose criminal acts by Nixon’s re-election committee, her own husband had her held captive, assaulted, and forcibly injected with drugs. Then the Nixon administration discredited her through a vicious campaign of slander and lies.

The slander and lies were successful. Ask anyone who was around back then for their impression of Martha Mitchell, and the opinion you’ll most often hear is that she was a nut, or a drunk, or both. That image of Martha Mitchell has persisted for fifty years.

And in 2017, President Trump gave a prestigious job to the former FBI agent who assaulted Martha Mitchell.

Martha Mitchell, January 1969 (Bettman Photo, Getty Images)

WIFE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

John Mitchell and Richard Nixon had known one another since the early 1960s. Mitchell was the preeminent municipal bond law specialist in New York City (if not the country), and Nixon was a name partner at a “white-shoe” law firm. On January 1, 1967 their law firms merged. Later that year Nixon decided to make another run at the presidency and Mitchell became his campaign manager.

John and Martha had married (the second marriage for each) in December 1957. By all accounts they were very much in love. Their daughter Marty was born in 1961. They lived in Rye, a New York City suburb, and Martha drove John to and from the train station every day. Mitchell’s work brought him into contact with Richard Nixon, which thrilled Martha, who convinced her husband, “a Kennedy man,” to become a Republican. It was she who persuaded him to become Nixon’s campaign manager in 1967. She soon regretted it when John devoted all his time to Nixon and very little to her and their family, and in 1968 she asked a lawyer to begin divorce proceedings. Shortly after that she entered a sanitarium for a few weeks − whether to “dry out” or to recuperate from exhaustion and emotional stress is disputed. Also unclear is whether she entered voluntarily or whether John Mitchell sent her there.

For citations to all facts and quotations, see Notes and Sources for the Silencing of Martha Mitchell: https://www.necessarystorms.com/home/notes-to-the-silencing-of-martha-mitchell

John Mitchell being sworn in as Attorney General by Chief Justice Earl Warren on January 22, 1969, while Martha Mitchell holds the Bible. Richard Nixon looks on. (Keystone/Getty Images)

A month after Nixon won the 1968 election he named Mitchell as Attorney General. Mitchell advocated no-knock entries into homes, no warrant frisking and wiretapping, preventive detention, and the use of Federal troops in Washington DC to suppress crime.

Upon taking office Mitchell ordered the Justice Department to drop its antitrust case against El Paso Natural Gas. El Paso had been a client of the Mitchell-Nixon law firm, and in the past six years had paid that firm legal fees of over $700,000.

Martha Mitchell was launched into the public eye when she appeared on the CBS Morning News a few days after the November 1969 anti-war Moratorium that had brought over half a million protestors to Washington. Martha said that when John Mitchell had looked out the window he’d remarked, “It looks like the Russian Revolution going on.”

Moratorium, November 15, 1969. Over half a million people in Washington DC (and hundreds of thousands more in other U.S. cities) protested the war. It’s still the largest anti-war demonstration ever held in this country.

In the next few days “holy hell broke loose,” Martha later said.

There was more to come. In August Nixon had nominated Clement Haynsworth to the Supreme Court. There was strong opposition based on his rulings upholding segregation and against labor; his nomination was opposed by the NAACP, the Rockefeller Republicans, the AFL-CIO, and a coalition of 125 religious, labor, welfare and civil rights groups. Nixon refused to withdraw the nomination and hearings continued for several months. John Mitchell suggested to Martha that she call some of her influential friends in Arkansas, her home state, “and tell them to put pressure on Arkansas Senator J. William Fullbright to vote for Haynsworth’s confirmation.” Martha did so enthusiastically. After her CBS Morning News appearance, word got out about those calls and another uproar ensued. But Martha was not upset because “[t]his time she’d only done what John had asked her to do” and President Nixon had told her both in a letter and a phone call “to keep it up, she was doing fine.”

Nixon originally considered her a “secret weapon” and John Mitchell called her his “unguided missile.”

Clark Mollenhoff, Special Counsel to Nixon, once explained that Martha’s comments were useful to the Nixon Administration because they expressed opinions that the Nixonians couldn’t publicly say.

Martha was, in other words, more of a guided missile.

Intending no disrespect or belittlement, I will refer to Mrs. Mitchell herein as “Martha” most of the time, partly for brevity, partly because she preferred informality, and partly because she almost seemed to be someone we knew back in those days. Even the stolid New York Times (and the Gray Lady was much stodgier 49 years ago) referred to her as “Martha” throughout a 1970 article.

October 2, 1970

Unlike almost every other woman married to a Cabinet official, Martha Mitchell was one of the most famous women in America and at one point “had a phenomenally high 76% national recognition factor in the Gallup poll.” She won approval from many Americans when she refused to curtsy to Queen Elizabeth II, explaining “I feel that an American citizen should not bow to foreign monarchs.” (A sentiment echoed by a good friend of mine, a one-time member of the Communist Party USA.)

She was known for phoning reporters unexpectedly and the press dubbed her “the Mouth from the South.” For Christmas one year Vice President Agnew gave the Mitchells gag gifts: “For Martha, a brand new Princess phone. For John, a padlock for a brand new Princess phone.”

Mitchell’s public remarks expressed humor at Martha’s statements, but in private he tried to restrict her access to reporters. “Sometimes the lengths to which the Attorney General went to control Martha’s exposure to the media were amazing,” writes her biographer, Winzola McLendon. Mitchell “managed to create the impression that he was an unfortunate but compassionate man saddled with a slightly flaky wife whom he adored too much to suppress. Martha didn’t see it that way. She claimed that it was at John’s request that she made most of the calls that turned out to be controversial.”

November 30, 1970

By 1970 Martha was becoming disillusioned with Nixon. McLendon writes that her “disenchantment with the Nixon Administration came early” because Nixon wasn’t ending the war as he’d given her to believe he would. Also, Martha had lobbied Nixon to appoint a woman to the Supreme Court, and his failure to do so was a disappointment. He had led her to believe that he would and she’d spoken publicly about it. When, in 1970, Nixon encouraged Lenore Romney to run for Senator, then ignored the election and gave Ms. Romney no support, Martha astutely noted that Nixon “didn’t want women in government any more than he wanted one on the Supreme Court.”

Another reason for Martha’s disillusionment was that she believed the White House was putting more effort into “getting its enemies” than dealing with the country’s problems.

When Martha’s comments began to sometimes differ from the policies of the Nixon administration, Nixon decided she had become a problem, and he discussed her privately with Haldeman. As early as May 1970, after the Mitchells appeared on “Sixty Minutes,” he told Haldeman that “Mitchell has to go unless he can solve the Martha problem.”

At a dinner given by renowned hostess Anna Chennault in the summer of 1970, a military officer just returned from Vietnam described boys of fourteen fighting alongside American soldiers, and Martha began sobbing. She “was terribly upset” and “had a debating society going on right there,” challenging the military man. When another guest talked about Nixon’s election, Martha said she wished he’d never been elected.

In September 1970 Martha was on Air Force One with the presidential party flying across the country. John was in the front area with Nixon, Bebe Rebozo, and Secretary of State William Rogers. Martha, bored, moved to the press compartment where reporters were playing cards. She ordered a Scotch and joined the game. Helen Thomas, the UPI White House correspondent, asked Martha about a fashion trend, and Martha replied, “Oh, Helen, why don’t you ask me about something important?”

“OK,” Thomas said. “What do you think of the Vietnam War?”

“It stinks,” Martha said. She said more, as reporters abandoned their card game and pulled out their pens and notepads. Among other comments, she blamed Senator Fulbright (who’d pushed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution through the Senate) and concluded, “We shouldn’t have gotten into the war in the first place. The Nixon Administration inherited it and they’re trying their best to get out of it.”

When Secretary Rogers got wind of the topic of conversation, he went to the press area and told Martha, “Why don’t you stick to law and order and I’ll take care of foreign policy?”

Martha never flew on the presidential plane again.

Martha’s son by her first marriage, Jay, an Army lieutenant, was in Vietnam in 1971, and she believed he had been sent there by the Defense Department only because he was her son − to “get back” at her, she told Helen Thomas. When she hadn’t heard from him in several months, she tried to find out what was happening but “couldn’t get anyone to speak to her.” She even called Defense Secretary Melvin Laird’s office twice but was rebuffed both times. She asked for help from Ms. Thomas, who got word from the UPI Saigon bureau that Jay had been in a combat zone with heavy fighting and numerous casualties but was now safe.

CREEP

In 1971 the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP, but known to history as CREEP) was set up. Martha began working at the CRP office in May 1971. She was much sought after for public appearances, and had an office where she and aides answered the massive amount of mail that she received.

J. Edgar Hoover, Martha Mitchell, Minnie Pearl, and John Mitchell at a dinner honoring Martha on May 24, 1971. Hoover was under siege. On March 8, activists broke into an FBI office in Media, PA and stole thousands of pages of FBI documents that revealed not only surveillance of the Left, but criminal acts committed against it, including sabotage, arson, perjury, and worse, under a program called COINTELPRO. Within days documents were sent to the national media, underground newspapers, radical groups, several members of Congress, and individuals who were being watched and/or investigated. On March 24 John Mitchell issued an urgent plea to the press not to publish information from the documents. In April Senator Muskie strongly denounced domestic surveillance of activists and proposed a domestic intelligence review board. Rep. Hale Boggs called for Hoover’s resignation. FBI agent Mark Felt wrote that this event was “the turning point in the FBI’s image.”

Despite a massive manhunt, said to be one of the largest in FBI history, the culprits were never caught. (Photo: CSUALPHA_05 CSU Archives/ Everett Collection)

CRP’s office was conveniently located at 1701 Pennsylvania Avenue, across the street from the White House. A mile and a half to the west was the Watergate Complex, which had opened to great fanfare in October 1965. The final structure, the Watergate Office Building, was completed in January 1971.

An odd historical fact is that many people who later became embroiled in the Watergate scandal lived at the Watergate complex, including Rose Mary Woods (Nixon’s secretary), Fred LaRue (long time Nixon adviser), Maurice Stans (Secretary of Commerce), Victor Lasky (columnist who later wrote a book about Watergate), Anna Chennault (see Notes), and many federal and White House officials. The Mitchells lived there as well.

The Watergate Complex. This photo was Government Exhibit One in criminal trial of Liddy and McCord (photo: NARA Record Group 21)

While working at CRP Martha became aware of “dirty tricks.” In 1971 she saw a file on the desk of Bart Porter, CRP’s scheduling director. The file was filled with information gleaned from spying on Senator Muskie, who was then the Democratic Party frontrunner. Early in 1972 John Mitchell tried to show her a campaign strategy book “filled with what he said were political espionage plans.”

When Nixon asked John to run CRP, Martha urged him not to. But he didn’t take her advice and resigned as Attorney General on March 1, 1972. His resignation supposedly had nothing to do with the fact that he was then being accused of perjury and corruption in the ITT matter (briefly explained in the Notes).

In March 1972, days after John Mitchell became the director of CRP, the Mitchells went to Florida for a vacation. To Martha’s surprise other men from the campaign were there and dominated John’s time.

She listened via intercom to the infamous March 30 meeting between Mitchell, Magruder and LaRue and heard them discussing budgets for wiretapping and other illegal acts of Operation GEMSTONE. All three men later gave different versions of that meeting, including whether Mitchell approved the plan and whether Haldeman and/or Nixon had participated by phone; but Martha said there was “no question if they were doing the dirty tricks, only the amount of money to be spent.” (Emphasis in original.)

In April 1972, John Mitchell met with CRP’s Security Coordinator, James McCord, and asked him to arrange security for Martha and the Mitchells’ daughter Marty, since they were no longer protected by FBI agents as they had been when Mitchell was the Attorney General. Over the next few weeks McCord himself personally escorted Marty to and from school and came to know Martha fairly well. He also spent time at the Mitchells’ apartment — to check it for bugs, he said.

Alfred Baldwin III testifying on May 25, 1973, to the Senate Watergate Committee. Supposedly McCord hired him sight unseen after plucking his name from the Society of Former FBI Agents roster, first to act as Martha Mitchell’s bodyguard, then to monitor illegal wiretaps from a hotel room across from the Watergate. (Photo: AP)

On May 1, McCord arranged for former FBI agent Alfred Baldwin III to be Martha’s bodyguard − or, according to Haldeman, “to handle Martha Mitchell” (emphasis supplied). They left for Detroit on AmTrak the next day. But one trip with Baldwin was enough for Martha; he was crude and incompetent, with disgusting personal habits. He was relieved as her security man and McCord assigned him to surveillance of the anti-war movement and to monitoring the Watergate bugs.

Martha “went through” several other security men before Steve King, a former FBI agent, was assigned on May 17.

In mid-June 1972 the Mitchells vacationed at Bebe Rebozo’s property in Key Biscayne, Florida. After that Martha intended to fly to New York for appointments, but Fred LaRue insisted she postpone her plans and join John Mitchell, the LaRues, and others in California for Republican fund raising events.

A WORD ABOUT FRED LA RUE

Fred LaRue was John Mitchell’s top aide and a close friend.

LaRue’s father Ike had gone to prison in the 1950s for fraud committed as a banker. When he got out, the family moved to Mississippi to look for oil. They found it, but Ike didn’t have long to enjoy it. In 1957 a small party that included Ike and his son Fred, then age 29, went duck hunting in Canada. Fred accidentally shot his father to death.

Fred LaRue testifying before the Ervin Committee, July 18, 1973. “Q: And what about the last $75,000? A: This came from Mr. Mitchell.” (Photo: theavocado.org; quote: The Watergate Hearings, ed. NY Times)

The family was extremely wealthy. For example, one of their oil fields was sold for $30 million in 1967, which is about $225 million in 2018 dollars. Among the ventures in which Fred LaRue invested in the late 1950s were casinos in Cuba. His timing was unfortunate. Within months, the Cuban Revolution occurred. Business at the casinos dried up and in 1961 they were nationalized.

LaRue was a member of the Republican National Committee from 1963 to 1968. He contributed heavily to Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, then got involved with Nixon. He was a long time friend of Senator James O. Eastland (D, Mississippi). LaRue was the architect, along with Strom Thurmond, of Nixon’s successful “Southern strategy,” which recaptured the southern states from the Democratic Party.

Mitchell hired LaRue, whose “official title was special consultant to the president,” for which he was paid one dollar a year. He later said “I basically reported to no one.” He was hired by CRP in early 1972 as Special Assistant to the Campaign Director. He was a key player in Nixon’s “dirty tricks” against radical activists as well as against Democrats, and became known as the Watergate “bag man.”

Martha Mitchell didn’t trust LaRue. When she was at Key Biscayne in March 1972 and her usual CREEP security guard had to leave, he “turned his gun over to Fred LaRue. ‘It frightened me out of my wits,’ Martha [said]…‘My God, this man had killed his own father in a hunting accident and that jerk gave him his gun!’”

24 year old Watergate security guard Frank Willis discovered the taped doors on June 17, 1972 and notified police, setting into motion a chain of events that toppled a president. Though hailed as a hero, he lived the rest of his life in extreme poverty and died of a brain tumor at the age of 52. (Photo: AP)

BURGLARY IN WASHINGTON AND ASSAULT IN NEWPORT BEACH

Just past midnight on June 17, 1972, as Friday night became Saturday morning, operatives of CREEP were caught breaking into the Democratic National HQ at the Watergate. John Mitchell and Fred LaRue, in California, got word early Saturday morning, and spent most of the day discussing the problem with Robert Mardian, CREEP’s lawyer.

That night, Saturday the 17th, the Mitchells attended a “Celebrities for Nixon” party in Beverly Hills. Other guests included John Wayne, Governor and Mrs. Reagan, Jimmy Stewart, Clint Eastwood, Jack Benny, Charlton Heston, and Zsa Zsa Gabor. After the party Martha told John she was angry at another snub by Pat Nixon as well as the lack of appreciation for her demanding schedule of fund raising and other activities on behalf of the Republican Party. She wanted John to quit politics. He agreed that he would, after the election in November, and that they’d return to New York and he would practice law again, which was all he’d ever wanted to do.

The CRP delegation moved their California sojourn to Newport Beach. John flew back to Washington on the morning of Monday, June 19. Before leaving he issued a statement denying complicity in or knowledge of the break-in.

On Monday, June 19, Martha read about the break-in in the Los Angeles Times. The article included a photo of James McCord, and quoted John Mitchell as saying that McCord “is the proprietor of a private security agency who was employed by our Committee months ago to assist with the installation of our security system…” Mitchell implied that he barely knew McCord.

James McCord about to rat out co-conspirators to the Ervin Committee, May 1973. “John Mitchell…gave sanctions to the Watergate operation by both the White House and the Attorney General’s office.” (The Watergate Hearings, ed. NY Times, May 22, 1973)

Martha knew better. John Mitchell was still in the air and she reached Magruder (who’d flown back to DC on Sunday on a chartered jet) and demanded to know why McCord was being “thrown to the wolves.” When she finally reached John, he said that people were trying to create a problem for CREEP but it wasn’t a big deal.

She found out from the TV news that the Democratic National Committee was suing CRP and the burglars for a million dollars. She kept trying to get more information, but John stopped taking her calls. On Thursday, June 22, she spoke to Fred LaRue, who informed her that she wouldn’t be able to speak to her husband. She told LaRue to give John a message: He had to leave politics immediately − not wait until November − or he’d never see her again; and she was going to call the press to report her ultimatum.

Helen Thomas of UPI described in her 1999 memoir what happened next.

Martha phoned Thomas at her home at around 6pm and told her: “I’ve given John an ultimatum. I’m going to leave him unless he gets out of the campaign. I’m sick and tired of politics. Politics is a dirty business.”

Suddenly Martha grew agitated and yelled, “You get away. Just get away.” The line went dead.

Thomas was alarmed and tried to call back several times, was unable to get through, and phoned the hotel’s switchboard operator, who told her that Mrs. Mitchell was “indisposed and cannot talk.”

John Mitchell’s mug shot. (Photo courtesy of The Smoking Gun.com)

Thomas then phoned John Mitchell. To her surprise, he was blasé and said several times that Martha was in no danger. “That little sweetheart. I love her so much. She gets a little upset about politics but she loves me and I love her and that’s what counts….I’ve promised Martha I’ll give up politics after this campaign.”

Thomas wrote that she later learned that John Dean was with Mitchell during the call, as were others, and “they had quite a laugh over it.” Thomas didn’t name the “others” but the meeting was attended by Mitchell, Dean, LaRue, Mardian and Magruder.

Meanwhile, back in Newport Beach, Steve King threw Martha across the bed and yanked the phone cord out of the wall. (In those days, phone lines were hard-wired into the wall, not simply plugged into an outlet; pulling one out of a wall wasn’t easy.) She fled to the adjoining room of the suite but he ran after her and pulled that phone out of the wall, too, then shoved her into her room and locked the door. She climbed onto the balcony to try to escape. King went after her and pulled her back inside. He also threw her down and kicked her.

The next morning she managed to slip downstairs but King saw her just as she reached the door. Another scuffle ensued, and it was so violent that Martha’s left hand went through the plate glass. She was badly cut. A doctor was called.

When the doctor arrived, Martha told him she was being held a political prisoner. The doctor later said there were security men milling about everywhere; he was told they were Secret Service, and that Martha had been drinking and was out of control. The doctor didn’t treat her hand. Instead, three men and the female secretary held Martha down on her bed and the doctor injected her in the buttocks with tranquilizers.

The drugs failed to sedate her and she again tried to get away; Steve King rushed over and slapped her hard. He ordered her to go back to her room. When she refused, he and the secretary carried her there.

John Mitchell finally called, but Martha refused to speak to him. He then got hold of Nixon’s personal attorney, Herbert Kalmbach, who lived in Newport Beach, and asked him to take over the situation. Kalmbach went to the hotel and brought Martha to a hospital so her hand could be stitched up. She returned to the hotel upon his promise to have the phones reconnected. They were not.

Meanwhile, Helen Thomas dictated a story for UPI that she says “got a fair amount of play” but mostly in the so-called “women’s pages.”

The NY Times ran the story on page 12 on June 23 with the headline “Martha Mitchell Would Like Her Husband to Quit Politics.” Watergate wasn’t mentioned. The article briefly describes the “abrupt” end of her phone call “when it appeared that somebody had taken the phone from her hand. She was heard to say, ‘You just get away.’ The connection was broken…” The Times didn’t describe her being assaulted and transformed the incident into a humorous anecdote, writing that her husband “expressed amusement at his wife’s turning to the telephone − her trademark as a public figure…”

A year later, Steve King was interviewed by the FBI and gave a rather different version of events, which is recounted in the Notes to this article. Over the years he’s occasionally been asked about the incident and says he won’t speak about it out of respect for the Mitchells’ privacy.

CAMPAIGN TO DISCREDIT MARTHA MITCHELL

After another day as a prisoner, Martha flew to New York with two family friends who’d come to Newport Beach upon John’s request.

On Sunday, June 25, Helen Thomas reached Martha in Westchester where she was staying. Martha told Thomas, among other things: “I’m black and blue. I’m a political prisoner.” “I love my husband very much, but I’m not going to stand for all those dirty things that go on.”

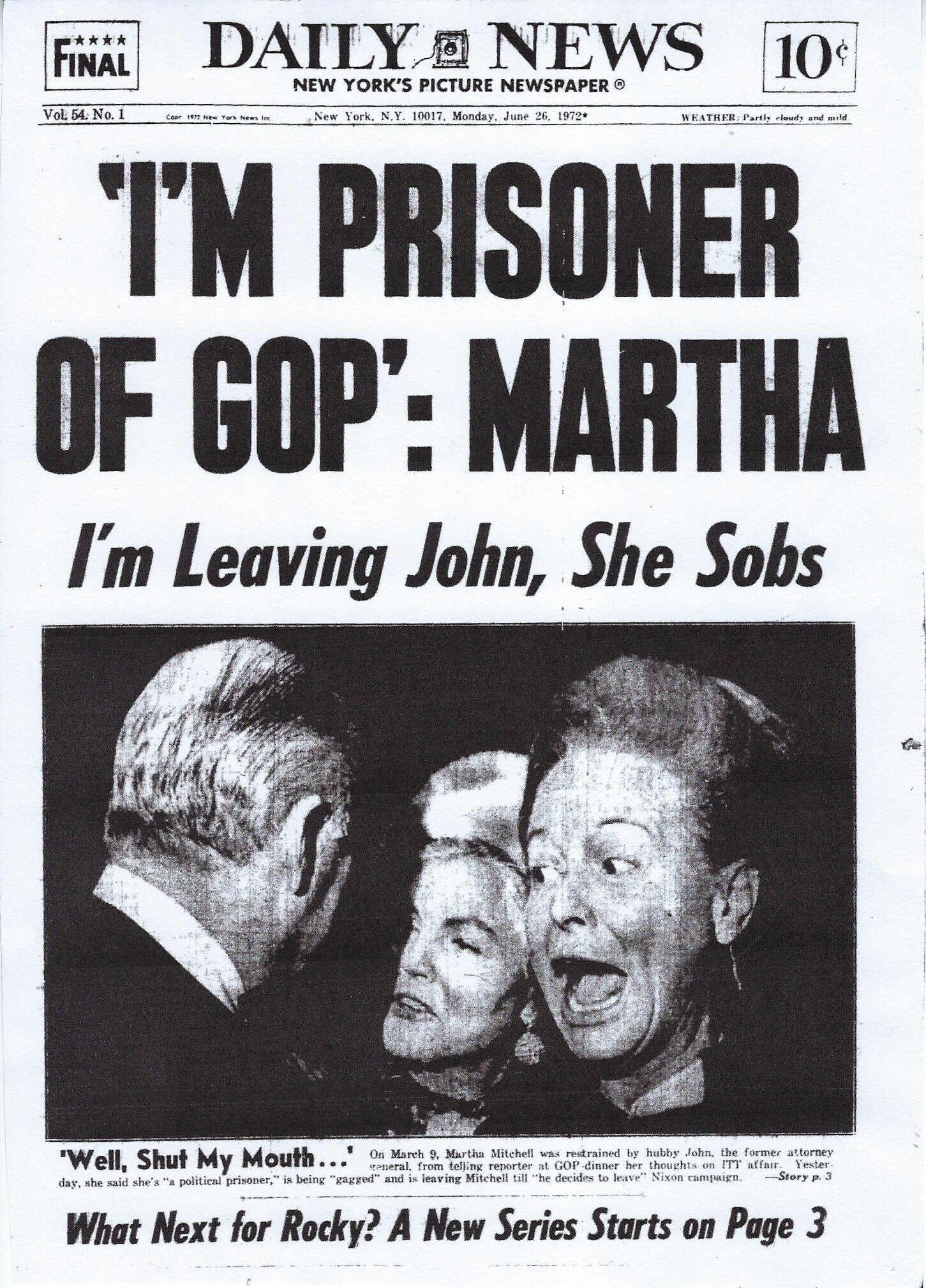

Ms. Thomas wrote another article for UPI and after it went out, Martha was besieged by reporters. Only the New York Daily News writer, Marcia Kramer, got through. Kramer described Martha as a “beaten woman” with black and blue arms; in Kramer’s opinion, the beating had been “a professional job.”

The Daily News article ran with a banner headline: “ ‘I’m a prisoner of GOP’: Martha” on June 26, 1972. But the illustration was a large photo of Mrs. Mitchell with her mouth wide open and the caption “Well, shut my mouth…” The article noted that her “hubby” was in the process of restraining her from talking about the ITT affair.

Still, this brought things to a crisis point. Martha had to be discredited.

The next day John Mitchell went to the White House and had a private conversation with President Nixon. Their conversation wasn’t recorded and has never been explained. Mitchell then retrieved Martha from Westchester and brought her home to Washington, and met again with Nixon. Then he announced that he was giving up politics for the woman he loved.

But as the White House tapes later revealed, Nixon, Haldeman and Mitchell decided that Martha’s public demands that Mitchell resign would be a convenient excuse for him to avoid the public eye.

At this point, the White House had not been implicated in the break-in or the nascent cover-up. The Watergate break-in was being attributed to over-zealous Cubans encouraged by a couple of rogue former intelligence agents.

Campaign button in 1972.

Both parties held conventions that summer in Miami Beach. At the Democratic convention in July, Martha received one vote for Vice President from the Maryland delegation, and the most popular button was one that read “Free Martha.”

The Republicans kept Martha away from their August convention.

Over the next few months Nixon, Mitchell, and various others carefully commented to the press about Martha’s “mental crack-up” and John’s admirable husbandly devotion and sacrifice. In September 1972 the Washington Star falsely reported that she’d had a nervous breakdown. Jack Anderson repeated that claim a year later. Pat Nixon at some point described Martha as “very, very ill.” A search of major newspapers from late 1972 on will return articles that follow the Nixon line on Martha Mitchell: she is alcoholic, unhinged, mentally disturbed.

Nevertheless, Nixon insisted that Martha attend a Republican fundraiser in September 1972 to appease her “constituents.” She did, and at the end of the dinner, guests frantically tried to reach Martha, knocking over chairs and reaching over tables to shake her hand or get her autograph, while ignoring Nixon.

Martha Mitchell upstages President Nixon at a GOP fundraiser in New York, September 1972, which he had insisted she attend. (Wide World Photos.)

Very few publications took Martha’s situation seriously, but at least one did.

On September 10, 1972 Parade magazine’s Walter Scott answered a reader’s question: it wasn’t Steve King who injected Martha Mitchell “in the upper extremity of her thigh”; if she had been injected, a nurse or doctor had done it. King was now in charge of CRP security, but on June 17 the position had been held by James McCord.

Martha immediately wrote a five-page letter to Parade, which was printed a month later, on October 22, 1972, in which she described the assault by King and injection by a doctor she’d never seen before. She added that the whole thing had been witnessed by her eleven-year-old daughter. (The entire letter is included in the Notes.)

Parade related that it had tried to contact Martha on June 16, 17, and 18 and that Steve King had promised to relay their messages; had tried to reach her several times over the next few months, but was unsuccessful; and contacted Steve King for his version, which “we largely used in our [article]. Mrs. Mitchell says we were taken in.”

Parade apologized to Mrs. Mitchell for its “inability to ferret out the entire truth of what, why, where, and when happened to her…We tried, Martha, but they wouldn’t let us get to you….go ahead and write your book. Suggested title: What Politics Did to Me.”

On September 21, eleven days after Parade’s initial downplaying of King’s assault of Martha Mitchell, Bob Woodward interviewed her. Woodward spends several pages in All the President’s Men recounting his method for getting into the building and into her apartment, then writes that they talked for 15 minutes. “The subject of Watergate made her visibly nervous,” and she essentially refused to answer his questions. “It had been a wasted trip.”

It didn’t occur to Woodward that Martha Mitchell didn’t trust him.

Meanwhile the pressure on John Mitchell was increasing. On October 5, 1972, the Washington Post reported that he had controlled a secret fund used to finance intelligence-gathering operations. The night before the story was to run, Post reporter Carl Bernstein called Mitchell to get his comment. Mitchell said: “All that crap, you’re putting it in the paper? It’s all been denied. Jesus! Katie Graham [Post publisher] is gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.”

The comment, minus the words “her tit,” ran in newspapers across the country.

Richard Nixon with his friend Bebe Rebozo in Key Biscayne. Rebozo’s Key Biscayne Bank was suspected to be a pipeline for Mafia money. The FBI designated Bebe Rebozo “a non-member associate of organized crime figures.”

Martha told a reporter that she was considering suing CREEP for being beaten up by two of its employees. She had learned that, contrary to John’s promise to fire Steve King and the secretary, they’d been promoted to higher positions in CREEP. John was even quoted in the press as praising King. “I don’t care whether [John] is pleased or not − I’ve had it,” Martha told the reporter.

On October 13 Senator Ted Kennedy ordered a “preliminary inquiry” into the Watergate bugging incident and political espionage and sabotage of the campaign. The next day the Judiciary Committee confirmed subpoena power.

On November 1, Mitchell roughed up Martha at their Watergate apartment, leaving large bruises on her arms and knocking a cap off her front tooth. She called her friend and later biographer Winzola McLendon, who came along with her Navy Captain husband. Martha confided that she was afraid she’d be involuntarily committed to a mental institution; after what they’d done to her in California, she believed the President and his people could do whatever they wanted to perceived enemies. No one was safe.

She also told McLendon that “John was behind everything that happened to me in California.” She asked McLendon to promise that if she didn’t hear from Martha for a full day, she’d start looking for her, and if she couldn’t find her, not to ask John where she was.

Yet she wouldn’t leave him, despite McLendon’s advice that she do so.

On November 7, Nixon won re-election in a landslide. It was the largest margin of victory ever in a presidential election. A few days later Martha called Helen Thomas and said, “If you don’t hear from me, call the police.”

On February 22, 1973, Nixon had a clandestine meeting with Senator Howard Baker (R, Tenn), the ranking Republican on the Senate Watergate Committee, to work out a strategy for the hearings that would keep the probe from reaching into the White House. Nixon said that the line should be drawn around CRP, which by now was defunct. If Baker or others on the Committee must question Mitchell, they had to bring out the facts about Mitchell’s “horrible domestic situation.”

Nixon told Senator Baker that Martha was “very sick, and John wasn’t paying attention” to his work, and for that reason the younger members of CRP (Nixon called them “these kids”) got out of control.

Portraying Martha Mitchell as crazy or an alcoholic therefore served two purposes: Nobody would believe what she said, and Watergate could be laid at the feet of John Mitchell.

In May 1973 Martha told Helen Thomas, “Nixon should resign. He has lost his credibility in the country and in the Republican Party. I think he’s let the country down.”

Helen wrote the story. John Mitchell issued a statement that it would be “ridiculous” for anyone to take Martha seriously. “I’m surprised and disappointed that a ‘news organization’ would take advantage of a personal phone call made under…stress…and treat it as a sensational public statement.”

Martha was defended by journalist Vivian Cadden in an article in McCall’s Magazine in July 1973: “Martha Mitchell: the day the laughing stopped.”

The excellent article points out that no one had taken Martha seriously a year ago; if they had, the Watergate scandal would have been exposed then. But “two swift and deliberate moves [kept] Martha Mitchell from [revealing]…the Watergate cover-up.”

Step One was to keep her in “virtual imprisonment” for a week; Step Two was to “establish a new image for Martha that would insure that anything she said would be discounted immediately. Martha Mitchell had to be transformed from an outspokenly amusing Cabinet wife to a ‘sick woman’ whose outbursts would not be taken seriously.”

Cadden wrote of the effect of the strategy: “Why make too much of anything Martha Mitchell says? Don’t we know her to be the official court jester, always good for an amusing little story with her late-night telephone calls, always good for a laugh?”

CONVICTIONS AND CONSEQUENCES

In September 1973, two months after Nixon’s refusal to turn over White House tapes to the special prosecutor and a month before the “Saturday Night Massacre,” John Mitchell moved out of the Mitchells’ apartment, taking their daughter with him. Friends have said that it was his refusal to break with Nixon that destroyed the marriage. Martha has been quoted as saying “He fell into the clutches of the king.”

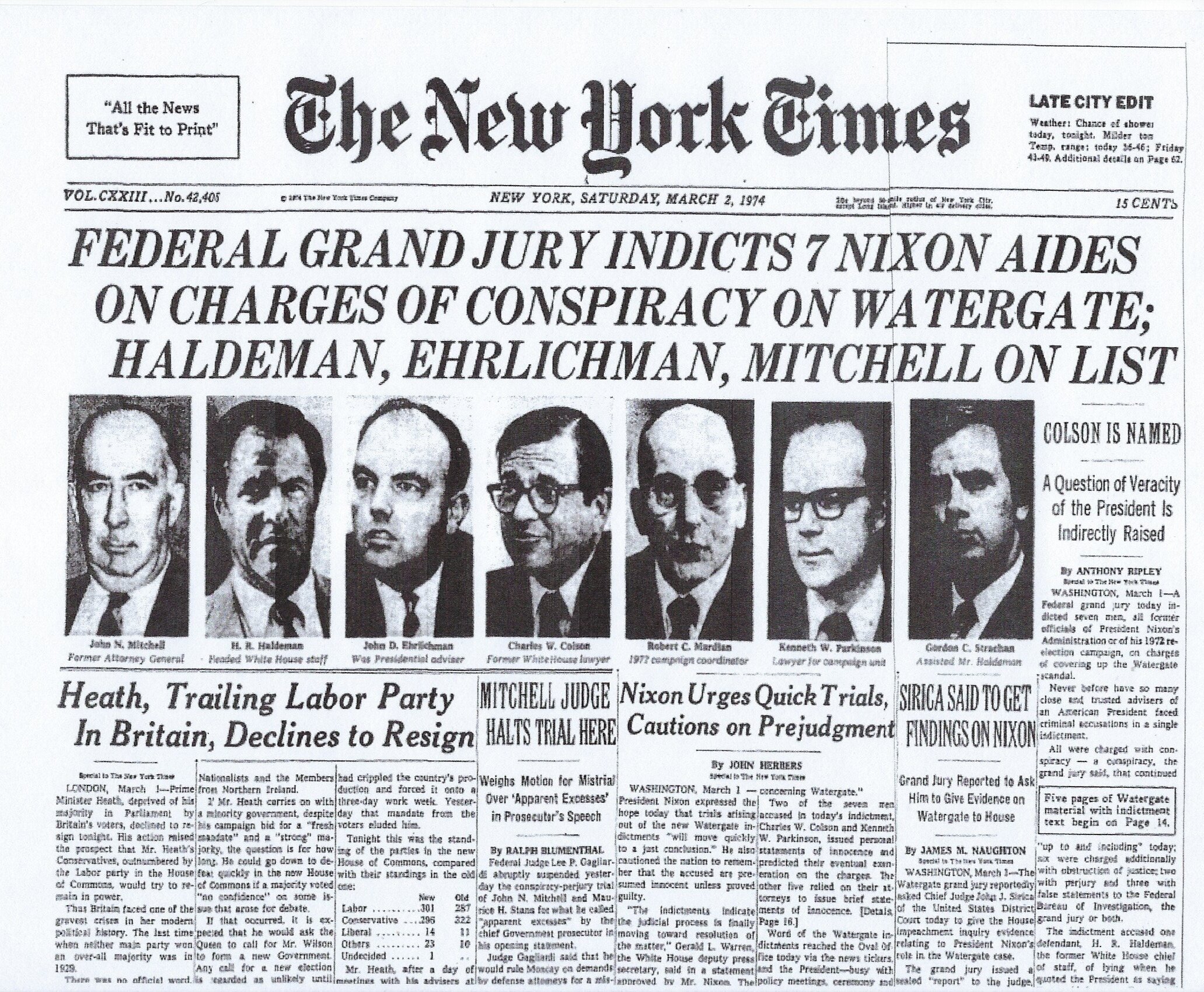

John Mitchell was indicted on March 1, 1974 on charges of conspiracy, obstruction of justice, and perjury.

Page One on March 2, 1974

After Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, fleeing the White House in a helicopter, Martha Mitchell was again a sought-after guest on talk shows and for interviews. She began writing a book with McLendon.

John Mitchell’s trial began in late 1974. He was convicted on January 1, 1975 on all counts and was sentenced to 30 months to 8 years. He told reporters: “It could have been a hell of a lot worse. They could have sentenced me to spend the rest of my life with Martha.”

To this day John Mitchell is the highest ranking Executive Official to ever go to prison.

On February 19, 1975, James McCord, who’d also been convicted, told a reporter: “Martha’s story is true − basically, the woman was kidnapped….they kept her locked up and she began to be afraid for her life.” McCord said that Nixon’s chief of staff, Haldeman, orchestrated “a great effort in the White House to discredit Martha Mitchell. They were extremely jealous of her and feared her because she was very candid.”

When told of McCord’s statement, Martha said:

“Thank God somebody is coming to my assistance. I was not only kidnapped but I was threatened at gunpoint, and you can put that in.”

In late 1975 Martha was diagnosed with cancer of the bone marrow. She told her doctor she suspected it had been brought on by the forcible injection in California in June of 1972, and he told her that her suspicion was “highly inaccurate.” But she never gave up the idea.

John Mitchell kept up Martha’s health insurance but stopped her alimony checks and she had to sue, eventually being rewarded a judgment of $36,000 for the past due payments. But the apartment and its maintenance was $2,300 a month. John failed to pay the court ordered judgment, leaving Martha penniless while suffering from terminal illness. On May 29, 1976, she signed a power of attorney so that two friends could retrieve jewelry from a safe deposit box, including her engagement ring. She wanted to sell the jewelry in order to pay her caregivers.

Two days later she was dead. She was 57 years old.

Her death was reported on page 1 of the New York Times.

At Martha’s funeral in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, an anonymous person sent a floral arrangement of white chrysanthemums that asserted “Martha Was Right.”

Photo: Henry Marx/Pine Bluff

On the fifth anniversary of her death, a life-sized bronze bust of her was unveiled in Pine Bluff with the inscription “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free.”

NIXON’S SLANDER CONTINUES

Nixon’s interview with David Frost, for which he was paid $600,000 and 20% of the profits, took place over a four-week period in spring of 1977. The nearly 30 hours were edited down to six and broadcast in May. Additional material was shown in September. Nixon’s comments about Martha Mitchell were shown in that last broadcast.

He told Frost that Martha had “said she was going to blow the whistle on everybody and that John was…being made a scapegoat…But we don’t need to go into that.” Then, only a few moments later, he confirms (but doesn’t admit) she was right: “….[I] said, you know, ‘Draw the wagons around the White House, Mitchell is the guy.’”

Nixon’s main revelation was that Watergate was Martha’s fault.

Richard Nixon before boarding the helicopter as he flees the White House August 9, 1974 (photo: Associated Press)

“John’s problem was not Watergate. It was Martha….She was an emotionally disturbed person….[T]he tempo of her calls [increased] and she busted her hand through a window out in, here in California, and all the rest…[H]e loved her. He knew she was emotionally disturbed. He knew it wasn’t just booze…If it hadn’t been for Martha, there’d have been no Watergate, because John wasn’t minding that store. He was practically out of his mind about Martha in the spring of 1972. He was letting Magruder and all these boys, these kids, these nuts run things. The point of the matter is that if John had been watching that store, Watergate would never have happened.” (Emphasis supplied)

Headlines in some newspapers the next morning: “Nixon Blames Martha Mitchell for Watergate.”

Nixon wrote in his memoir that he believed some reporters

“…deliberately exploited Martha Mitchell during this period [1972]. Months later it would become clear to all that her wild claims that she had a manual containing procedures for the Watergate break-in and that she herself knew all the details were simply ploys to get attention. But even at the time it was obvious to those who came in contact with her that she had very serious emotional problems…”

He concludes (quoting his diary):

“Without Martha, I am sure that the Watergate thing would never have happened.”

THE RETURN OF A CREEP

Stephen B. King, appointed Ambassador to the Czech Republic in 2017 by President Trump. In the confirmation hearing he was not asked about his assault of Martha Mitchell in 1972 by any member of the bipartisan Foreign Relations Committee. (Official photo, U.S. Embassy in the Czech Republic)

On December 11, 2017, Newsweek Magazine noted that presidents have historically awarded ambassadorships to people with no diplomatic experience but a good record for raising campaign money, and that the newly appointed US Ambassador to the Czech Republic was just such a person. He was a longtime Republic Party official and supporter, a close friend of Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, and had been a business partner of Congressman Ryan’s brother.

The headline of Newsweek’s article: “Trump Ambassador Beat and ‘Kidnapped’ Woman in Watergate Cover-up.”

This new ambassador is Stephen B. (Steve) King − the former FBI agent who imprisoned and assaulted Martha Mitchell.

During King’s confirmation hearing on August 1, 2017 before the bipartisan Foreign Relations Committee, he “was not asked about his alleged role in roughing up Mitchell to keep her from exposing McCord’s connection to CREEP.” Members of that committee are listed in the Notes.

MARTHA MITCHELL’S LEGACY

To this day, Martha Mitchell is often described in the mainstream media as an emotionally disturbed alcoholic. For example, in 2013 in a disparaging opinion piece about Helen Thomas, the New York Post wrote of Thomas’s

“…phone conversations with Martha Mitchell, the emotionally disturbed wife of Watergate-era Attorney General John Mitchell. Mrs. Mitchell had a habit − owing in part to her reported alcoholism − of getting drunk and telephoning whoever would listen to her rants. Most reporters stopped exploiting Mitchell once it became clear how ill the woman was.”

A play by David Wolpe called “The Unguided Missile” was described in a 1989 New York Times review as presenting Martha as “a virago gone haywire” rather than “a protector of democratic principles.”

James Rosen’s 2008 biography of John Mitchell, The Strong Man, attacks Martha viciously, describing her as “sick, mean and ignorant,” an “aging belle [with a] fragile psyche,” a “rich eccentric” with “long standing problem with alcohol,” “unstable,” “prone to violent bursts of alcoholism.” He writes of the 1971 incident on Air Force One that Martha went to the press area “unaccompanied by her husband or some other sane person” and “sneered” at Helen Thomas. Secretary of State Rogers “gingerly” tried to rein Martha in.

Rosen calls journalists sympathetic to Martha “opportunistic partisans and dowdy society columnists.” McLendon is “Martha’s gossipfrau and ersatz Boswell.” As to the incident in November 1972 when Martha says John “punched me with a clenched fist in the mouth,” Rosen writes that “if history offers any guide, however, Martha most likely lunged at her husband and hurt herself in the process,” citing as evidence “her unfortunate swing at Steve King” in Newport Beach.

Rosen worked at Fox News from 1999 until 2017, when he left after three female co-workers accused him of sexual harassment.

A growing number of people and media outlets have come to respect Martha Mitchell. Among them:

—The 2017 Newsweek article by Jeff Stein on Steve King’s confirmation as Ambassador to the Czech Republic

—Leon Neyfakh in the Slow Burn podcast, Episode One, “Martha,” November 28, 2017

—A play by Jodi Rothe, “Martha Mitchell Calling”

—In 2019, shooting was to begin on a movie written and directed by Diane Ladd called “Martha: Woman Inside,” with Martin Scorsese as Executive Producer and David O. Russell as a producer.

—After this article was written, an eight-episode television series was produced about Martha. The producers said the series is based on the Slow Burn podcast. “Gaslit” stars Julia Roberts as Martha Mitchell and Sean Penn as John Mitchell, and will premiere on Starz channel on April 24, 2022.

—Most importantly is a documentary by Anne Alvergue and Debra McClutchy, “The Martha Mitchell Effect,” released in late 2022. In January 2023 it was nominated for an Oscar in the category Best Documentary Short. This extraordinary film, which can be seen on Netflix, tells the story of Martha Mitchell almost entirely through archival footage.

Even the profession of psychology has recognized that Martha told the truth.

There is a process whereby a mental health professional mistakenly diagnoses a patient’s accurate perception of improbable events as delusional, even if the patient has no history of delusion. This happens when the health care professional fails to verify whether the events actually took place.

In 1988, psychologist Brendan Maher gave this process a name: the Martha Mitchell Effect.