The Hazardous Life of Helen Holmes

Helen Holmes and J.P. McGowan were my great grandparents. Both died before I was born. Family lore was meager and most of what I know about them has come from research.

Helen Holmes was a silent movie actress best known for the 1914-15 serial The Hazards of Helen. She specialized in daredevil stunts involving trains; hence her nickname “the Railroad Girl.”

Helen Holmes was featured in the Baltimore & Ohio Employees Magazine. Date unknown.

Helen was a fearless, competent, and independent woman at a time when the suffrage movement was on the verge of finally gaining the vote for women. Her life and career reflected the situation of the feminist movement: she was admired and extolled for breaking new ground for women, but suffered the backlash against those values ten years later.

According to an Illinois birth certificate issued in 1942 at the request of a relative, Helen was born on June 19, 1891 in Chicago. But neither year nor place is certain. Her birth year is often given as 1894, including on her gravestone, while some documents list it as 1892; and in the 1930 census, Helen reported her birthplace as South Bend, Indiana.

She was the third child of Louis R. Holmes and Sophie Barnes, both from Indiana. Louis worked for the Illinois Central Railroad, later for the Chicago & Eastern Illinois. Helen told an interviewer in 1915 that she was born in Chicago, grew up in South Bend, and attended the Art Institute in Chicago; when she “broke down because of overwork” her brother invited her to his ranch in the Funeral Mountains (near Death Valley). She loved ranching and learned to ride and rope. Her background has been recounted differently in other movie magazines and articles, which say that she attended a convent school in Chicago and modeled for Santa Fe Railroad posters, and that in 1910 her brother’s illness necessitated that the family move to Death Valley, where Helen learned to pan for gold and reportedly lived with Indians for a time. All versions agree that when her brother died she went to Los Angeles. (Some biographies put her in New York acting for the theater, but these are mistaking her for a Broadway actress of the same name.)

Photoplay magazine February 1916. The caption reads in part: “Helen Holmes, heroine of the ‘Hazards of Helen,’ one of the most thrilling and successful series of melodramas ever screened…”

1912 was an eventful year for Helen. She met Mabel Normand and, through her, was “discovered” by Mack Sennett and signed by Keystone. In 1913 she appeared in Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life, directed by and starring Sennett, along with at least 17 more movies. That year she met the man who would become her creative and life partner: J.P. (Jack) McGowan.

Jack was an Australian whose colorful life had already encompassed near death in the Boer War, training horses to reenact that war for the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, possibly fighting alongside Pancho Villa in Mexico, and making epic movies filmed on location in Egypt, Jerusalem, and Ireland.

Helen signed with Kalem Studios, where Jack had worked since 1908. The pace of movie making in those days was astonishing. In 1914 alone, she acted in 26 movies. Most were railroad dramas; Helen was known as the Railroad Girl even before the first episode of The Hazards of Helen was released on November 14, 1914.

Their personal connections to railroads enabled Helen and Jack to give realism and accuracy to their films. Jack was born in the railroad junction town of Terowie (South Australia) and grew up in gritty Camperdown; his father worked on locomotive crews all his life, and his grandfather had been a locomotive engine driver in Scotland. Helen had learned as a girl how to drive an engine. After hearing a telegrapher jeer at the “fake telegraphing they saw in pictures”, she learned how to send telegraphs.

Magazines retroactively reported that Jack and Helen had married in 1912, or 1914, or 1915. No marriage certificate has been found. One magazine (Picture Play Weekly, July 10, 1915) said the opposite: “Helen Holmes, the daring railroad actress of Kalem, is performing more hazardous stunts every day. She has ventured almost everything except marriage.”

Hazards of Helen crew in 1914. Front row L-R, J. P. (Jack) McGowan, Helen Holmes holding her dog Casey, and Leo D. Maloney. (Photograph courtesy of Larry Telles)

Hazards was the longest-running of all of the serials, and differed from them in that it was actually a series. Each episode told a complete story, rather than having a cliff-hanger ending to be continued in the next installment. A more significant difference was that the Helen character (as in many serials, the heroine and star shared a first name) was not a damsel in distress. Helen rescued others more often than being rescued herself. She was quick-thinking, risk-taking, and had a deep sense of justice.

In the brochure for Treasures from American Film Archives, Scott Simmon wrote:

More than any other serial, however, the remarkable 119-episode Hazards of Helen…was an adventure of the workplace, conveying a no-nonsense feminism that subsumed overt politics within action stories about a woman’s capacity to do her job, and then some!

As described by writer Shelley Stamp:

“Hazards of Helen stresses the heroine’s acts of daring and physical prowess. The heroine is a humble telegrapher compelled to perform feats of extraordinary courage when she pursues runaway trains and fleeing bandits in situations that showcase her extraordinary athleticism…matched by a keen intelligence. She is unusually observant about the goings-on in her station, meaning that she is often the only character cognizant of danger and the only one capable of staging a rescue…Helen is a woman of true strength and independence rare among serial heroines.”

Helen Holmes on the cover of Photoplay, March 1915. The accompanying article is “The Girl on the Cover and Her Director.”

Helen acted in all but two of the first 48 episodes, wrote at least one, and directed several when Jack was in the hospital. She was extremely popular, appearing in almost every issue of the movie magazines, sometimes on the cover. She performed many (though not all) of her own stunts, including riding a balky horse down a steep cliff and plunging into the river; driving a car from the San Pedro pier onto a barge (the fourth attempt succeeded); escaping on an aerial steel cable and dropping to the roof of a boxcar going 20 mph; leaping from a burning building; jumping from the roof of one moving train to another; riding a motorcycle off a bridge while trying to catch a runaway train; and dropping from a trestle into an automobile. In her off time she liked to race cars, sometimes entering using only an initial to bypass rules forbidding women competitors.

The dangers she faced were real. Filming an episode of The Lost Express, she was trapped inside a burning train car. In another, she was in a truck when the brakes gave out on a steep grade and the truck crashed; she barely escaped serious injury. She nearly lost an eye that was punctured by cactus thorns. According to family lore, so far unsubstantiated, she lost a thumb while leaping from a galloping horse to a moving locomotive.

Her strength was real, too. A 1915 Photoplay article said that “[Helen] wears pretty gowns and is very proud of the fact that she can burst the sleeves of any of them by doubling up her biceps. Helen ‘shows her muscle,’ and zip-p-p! goes the dress goods.”

The feminism of Hazards is clear and uncompromising. The plots revolve not around the heroine’s romances, but her heroics and her battles with discrimination. In Episode 13, “Escape on the Fast Freight,” the telegraph office is robbed and the boss fires Helen, stating that from now on, “male operators only will be assigned.” Leaving work, Helen spots the two robbers on a train. She drops onto the train from above, alerts two railroad workers, and when they are unable to capture the robbers, she chases one down and fights him on top of the train. They fall into a river and when the robber attempts to flee, Helen tackles him. She is reinstated in her job.

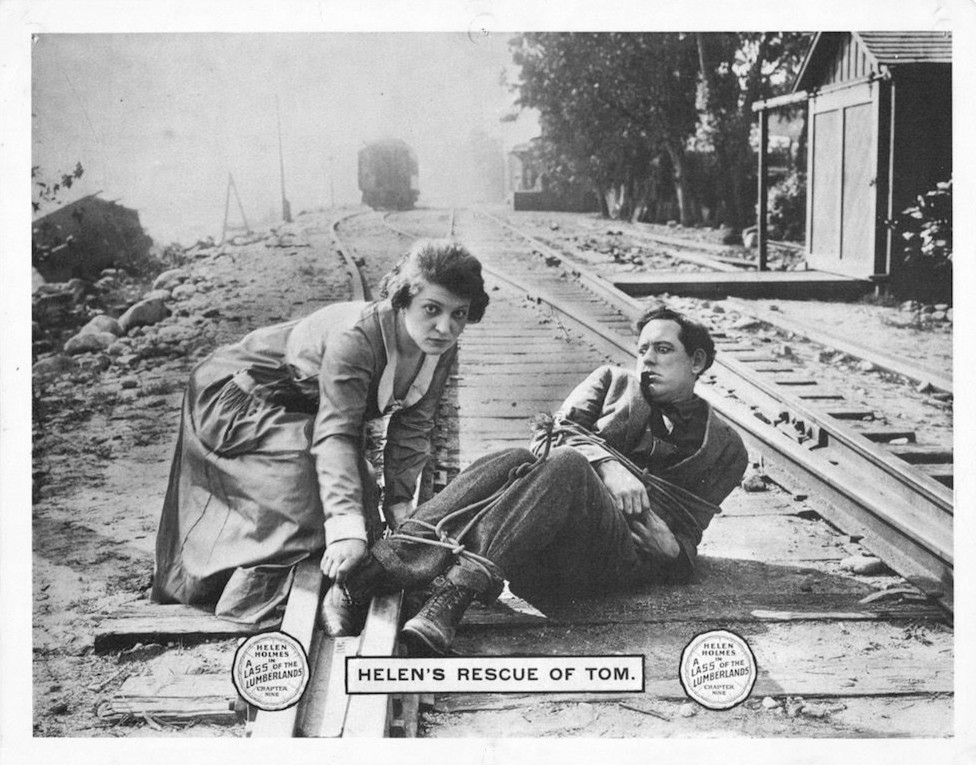

Lobby card for Lass of the Lumberlands.

Helen co-directed that episode with her co-star, Leo Maloney, because Jack was in the hospital with two broken legs (having fallen from a telegraph pole during the filming of a Hazards episode in December 1914). She was described in Moving Picture World as “managing the company” in Jack’s absence; the magazine also said she “writes scripts and does most of the work.” These roles were uncredited.

Helen Holmes noted that strong active roles were only available to women if they wrote them themselves. “Nearly all scenario-writers and authors for the films are men; and men usually won’t provide for a girl things to do that they wouldn’t do themselves. So if I want really thrilly action, I ask permission to write it in myself.”

Helen Holmes and the crew of The Lost Express at a rail yard, 1917 (photo courtesy of Mark Murphy, whose great-uncle was J.P. McGowan’s assistant, L. Virgil Hart)

Helen and Jack left Kalem in 1915 for unknown reasons. Both spent a few months working for Universal Pictures, which inexplicably assigned Helen to scenario writing and never began the serial they had promised her, and had Jack directing one-reel non-serials. A few months later they left Universal and formed Signal Film Corporation, specializing in railroad pictures. They immediately set to work filming The Girl and the Game; its first episode was released on December 13, 1915. Describing one of the car chase scenes in The Girl and the Game, an author wrote that “Helen controls the wheel, while her three brawny male buddies are relegated to mere passengers.”

The frenetic pace continued. From 1915 through 1917 Helen starred in eight movies and five serials, including Episodes 8 through 48 of The Hazards of Helen.

Released in 1916 were Judith of the Cumberlands (9 episodes), The Diamond Runners (a five-reeler written and filmed during a Hawaiian vacation), and the 15-episode Lass of the Lumberlands, filmed in various California locations including Mendocino, Arcata, Yosemite, and the gold rush town of Sonora.

That year, newspapers reported that Helen had adopted a baby. She told movie magazines that, for a scene in Lass of the Lumberlands, she’d borrowed a baby from an orphanage, fell in love with the baby and decided to keep it. Helen’s granddaughters, however, were told that the baby was the daughter of J.P. McGowan and his housekeeper, and that Helen agreed to raise the child as her own. The truth may never be known, since adoption records are sealed in California. In any event, Dorothy Holmes McGowan was born on December 17, 1915 and Helen reared her.

Helen Holmes and daughter Dorothy in 1917. When a magazine asked Helen her plans for rearing Dorothy, she replied that her daughter would be “dressed in a pair of overalls and play[ing] with a monkey wrench.” It didn’t take. Instead, Doro became a model and “glamour girl” who dressed up even at home. When she visited us she would come to breakfast fully made up, wearing a silk dressing gown and high heeled mules. This photograph may be the last time she was ever seen in overalls. (Photograph: author’s collection)

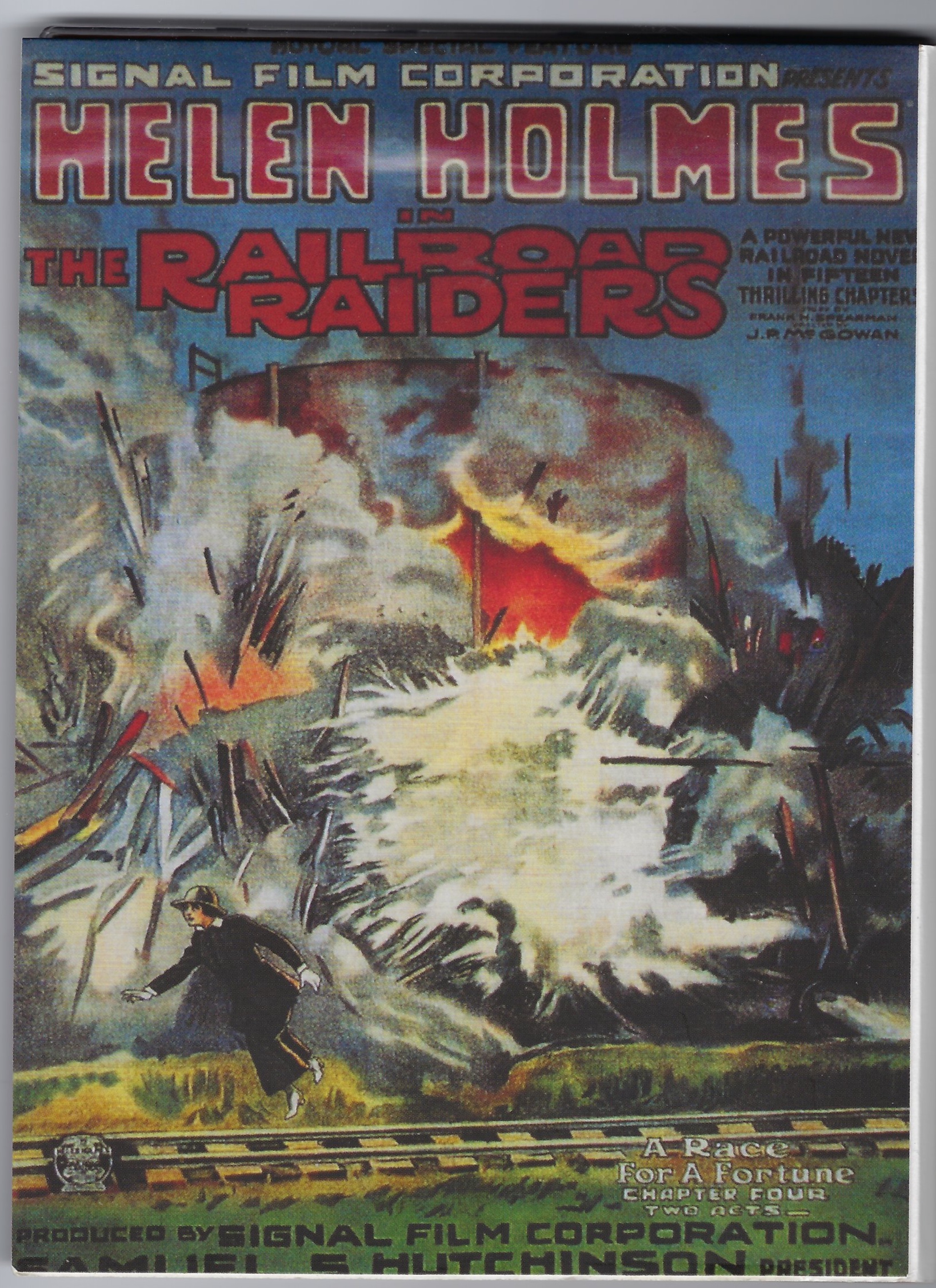

In 1917 Helen and Jack made the serials The Railroad Raiders (15 episodes) and The Lost Express (15 episodes). The California State Fair in September 1917 held a Helen Holmes Day, staging a train wreck in her honor. Two locomotives going 40 miles per hour headed toward each other. Before a crowd of thousands, Helen jumped from one of the trains into an automobile; “a few seconds later, the two trains were a mass of twisted steel and iron.”

Also in 1917 Helen bought a ranch in Utah with stock including chickens, horses, cows, pigs and goats. She told Photoplay she hoped to be a cattle queen someday. It’s not known whatever became of this ranch.

The break up of Helen and Jack was reported in the June 2, 1918 Los Angeles Times with the memorable headline “Helen Holmes Principal in a Domestic Smash-Up.” At about the same time Mutual Film Corporation, which had financially backed Signal and distributed its films, collapsed. Signal went with it.

These two events greatly impacted Helen’s career. She made no films in 1918 and only one in 1919. The next year she signed a contract with Harry and Albert Warner to make films under Helen Holmes Productions and released one feature, The Danger Trail, in 1920. She lent the Warner brothers $5,000 to complete production of her serial The Tiger Band and ultimately sued them after they did not repay her. By 1921 Helen had given up on producing and returned to acting. She appeared in films with William Desmond, Hoot Gibson, and Jack Hoxie as well as reuniting with Jack McGowan. Meanwhile, continuing her lifelong affection for dogs, she raised Irish terriers, training them for the movies. She and one of her terriers were in the Hoot Gibson movie Forty Horse Hawkins.

By the 1920s women had the vote and the spirited daredevil was no longer the role model for young women. Author Lynne Kirby cited the “Helen” character as the most vivid example of the transformation from independence and athleticism to daintiness, dependence on men, and the subsidiary role of inactive daughter or pining sweetheart. And in fact some of Helen’s movies from the 1920s are, when compared with Hazards, rather startling.

Helen and Jack briefly reunited but by 1925 they had separated as a couple for good. In March 1925 Helen married stuntman Lloyd Saunders in Fort Worth, Texas, two weeks after meeting him.

But Helen and Jack’s professional alliance endured. They made several pictures beginning in 1921, including the 1923 shipwreck drama, Stormy Seas. In 1925 they made five features. One, Webs of Steel, is one of the more unusual films of the era ─ the Helen in this movie is the Helen of old: strong, intelligent, fearless. She rescues a child and a puppy on a railroad trestle while wearing high heels.

Family photo of Dorothy. She appeared as an extra in several films; was a floor model and later the Fur Department manager at I. Magnin; and worked as a hostess at the Brown Derby. Her third (and last) marriage, to Dante Barone, was her happiest. They lived in Los Angeles. (Photo: author’s collection)

In 1926, Helen, Lloyd Saunders, and Dorothy moved to Sonora, California, a town Helen knew from having filmed there. The 1930 census listed them in a ranch west of town and a local newspaper mentioned Lloyd as a contestant in the annual rodeo in May. But by 1932 Helen and Lloyd had returned to Hollywood. Doro stayed in Sonora to finish high school and “boarded out” with a local family. She graduated in June 1933 and married Leland “Scotty” Burns, whose family had been in the area since the gold rush. They had two daughters.

Newspapers of the late 1930s talked of Helen’s attempted comeback after a ten-year retirement. But the backlash against the portrayal of strong women continued; a Los Angeles Times columnist wrote in 1936: “There are no more serial queens…Helen Holmes, Pearl White and others have long since retired, and the ladies of the serials now prefer to let their menfolk wear the pants.”

Helen had a part in Poppy with W.C. Fields and bit parts, many uncredited, in other movies. She made occasional public appearances to promote the movie industry and in 1938 was elected president of the Riding and Stunt Girls of the Screen, which initiated collective bargaining for stunt women.

Helen did not make a fortune in the movies. In the late 1940s she operated a small antique business from her home, which she was only able to keep by signing it over to the Motion Picture Relief Fund in a life estate. Lloyd Saunders died in 1946. A few years later Hedda Hopper reported that Helen was very ill. She had suffered lung problems all her life and had had pneumonia at least four times between 1914 and 1924.

Helen died on July 8, 1950. The death certificate listed the cause as pulmonary tuberculosis, but newspapers announced her death as due to heart attack, perhaps because tuberculosis still carried a strong stigma.

J.P. McGowan went on to direct and act in hundreds of films, mostly B westerns. He directed John Wayne in his first major role, a 1932 cliffhanger serial called The Hurricane Express. That was Jack’s final railroad drama. He served as Executive Director of the Screen Director’s Guild from 1938 to 1950. He died in March 1952 and was survived by his second wife, Kaye, and his daughter Dorothy and her two daughters.

Stunt Love, a documentary about J. P. McGowan and Helen Holmes made by the Australian company Closer Productions and directed by Matt Bate, was released in February 2011 and premiered at the South Adelaide Film Festival. It has also been screened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tiburon (California) International Film Festival, the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, and the Rosendale Theater Sunday Silent series (Rosendale, NY).

SOURCES

Books:

John McGowan, Hollywood’s First Australian: the Adventurous Life of J. P. McGowan, the Movie Pioneer They Called ‘The Railroad Man’ (Adelaide, South Australia: Display Visions Productions, 2016). This book is a must read for anyone interested in Helen, Jack, or silent movies.

Shelley Stamp, Movie Struck Girls (Princeton University Press, 2000)

Lynne Kirby, Parallel Tracks (Duke University Press, 1997)

William Drew, Speeding Sweethearts of the Silent Screen, an online book; no longer accessible.

Periodicals:

Jake Hinkson, “The Girl at the Switch,” Mental Floss Magazine, Winter 2013 (http://www.mentalfloss.com). A modified version of this article is available at https://www.neatorama.com/2015/01/02/Helen-Holmes-The-Girl-at-the-Switch/

Elisa Black, “The Terowie Tearaway,” The Sunday Mail (Adelaide, South Australia), February 27, 2011. https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/south-australia/the-terowie-tearaway/news-story/3118234fa74081d66c9e8433296d6817

Studio photograph of Helen Holmes inscribed to her granddaughter Valerie (my mother) in 1949.

Archives:

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Billy Rose Library, Robinson Locke Collection, Envelope 737.

Archives of the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Chicago Tribune.

Archives of Photoplay, Motion Picture Magazine, Moving Picture World, and Picture Play Weekly, collected and maintained by the Media History Project (http://www.mediahistoryproject.org); the database is searchable.

Other:

Stunt Love, the short documentary. The trailer may be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c20S4Ytrggo

The Silent Hall of Fame, http://www.silent-hall-of-fame.org/ , which has links to most extant Helen Holmes films, and which includes a version of this article, originally written for the 2011 film festival “The Two Helens” at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum.

The Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum (near Fremont, CA) is a treasure for silent movie buffs. In addition to screenings and guest appearances, the Museum has a wonderful store that offers many silent films on DVD. Niles was the site of Broncho Billy’s Essanay studio. http://nilesfilmmuseum.org

Women Film Pioneers Project, profile of Helen Holmes at: https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pioneer/ccp-helen-holmes/

Treasures from American Film Archives III, Social Issues in American film, 1900-1934, Program 2, New Women (Scott Simmon wrote a summary of Hazards of Helen episode 13, The escape on the fast freight.) https://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/treasures-iii-social-issues-in-american-film

The George Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY maintains a collection of more than 28,000 films from “the early experiments of Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers to the present.” http://eastman.org.

The Margaret Herrick Library at UCLA is devoted to the history of motion pictures and has a large (and non-circulating) reference and research collection. http://www.oscars.org/library/collections.

A short film of Helen and Dorothy (age about three) can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IIwTmIi-etY. (at the 11:30 mark). (Photoplay Magazine Screen Supplement #2, 1919, from the film collection of EYE, Amsterdam.

Few of Helen Holmes’s films survive. They include:

Hazards of Helen episodes through #48, after which Helen Gibson took over the Helen role:

#9, “The Leap from the Water Tower,” widely available online.

#13, “Escape on the Fast Freight”

#26, “The Wild Engine”

#33, “In Danger’s Path”

Feature films:

Webs of Steel (1925)

The Lost Express (1926)

Crossed Signals (1926)

Photoplay magazine, March 1915

![Helen and daughter Dorothy in 1917. When a magazine asked Helen her plans for rearing Dorothy, she replied that her daughter would be “dressed in a pair of overalls and play[ing] with a monkey wrench.” It didn’t take. Instead, Doro became a model an…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d260e430fb0cf0001baa0f7/1563033703414-P5XQRZKINEUMMEG71SVI/HH_Dot_train+1.jpg)